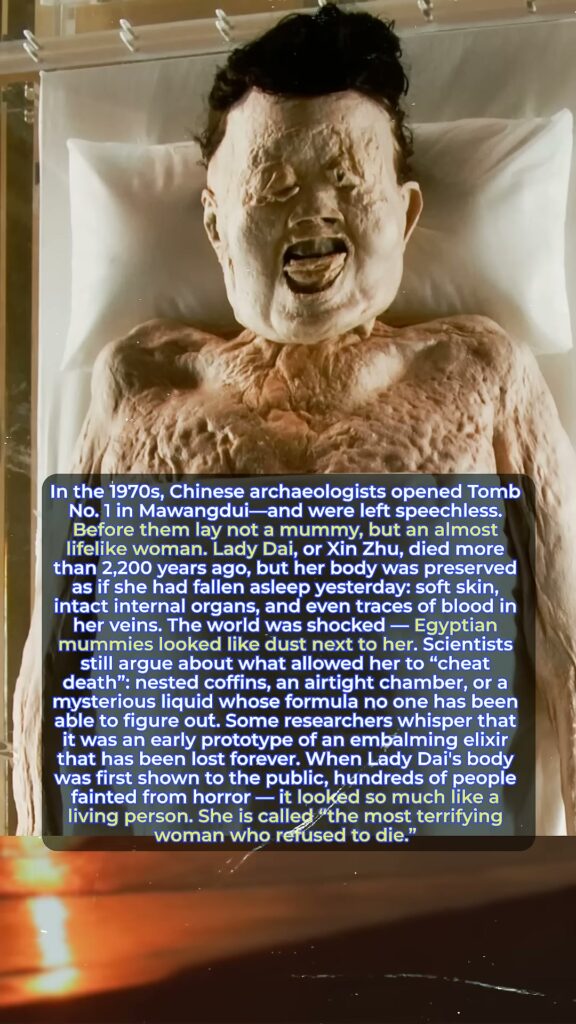

“In the 1970s, Chinese archaeologists opened Tomb No. 1 in Mawangdui—and were left speechless. Before them lay not a mummy, but an almost lifelike woman. Lady Dai, or Xin Zhui, died more than 2,200 years ago, but her body was preserved as if she had fallen asleep yesterday: soft skin, intact internal organs, and even traces of blood in her veins. The coffin was soaked—Egyptian mummies lacked fluid when scientists got to them. Scientists still argue about what allowed her to ‘cheat death’s ire.’ The fluids, the coffin, the chamber, or a mysterious liquid whose formula no one has been able to figure out. Some researchers whisper that she is an early prototype of an embalming elixir that has been lost forever. When Lady Dai’s body was first shown to the public, hundreds of people fainted from horror—it looked so much like a living person. She is called ‘the most terrifying woman who refused to die.'”

In 1971, deep beneath the earth in Mawangdui, Hunan Province, Chinese archaeologists uncovered a tomb that would rewrite the boundaries of preservation. Inside Tomb No. 1 lay the body of Xin Zhui, also known as Lady Dai, a noblewoman of the Western Han Dynasty who died around 168 BCE. But what stunned scientists wasn’t her status—it was her condition.

Unlike the desiccated remains of Egyptian mummies, Lady Dai’s body was soft to the touch, her skin supple, her veins still containing traces of blood. Her internal organs were intact. Her joints could bend. Her face looked eerily lifelike, as if she had simply fallen asleep. She became known as the best-preserved human mummy in history.

The preservation was so uncanny that when her body was first displayed, hundreds of visitors fainted, overwhelmed by the realism. She was dubbed “the most terrifying woman who refused to die.”

Scientists have spent decades trying to understand how this miracle of preservation occurred. Her body was found in a nested coffin system, sealed within four layers and submerged in a mysterious reddish liquid. The tomb chamber was airtight, with a stable temperature and humidity. Some speculate that the liquid was an embalming elixir, a formula lost to history.

Lady Dai’s tomb also contained over 1,400 artifacts, including silk garments, lacquerware, and medical texts. These items revealed her life of luxury—and her declining health. Autopsies showed she suffered from obesity, diabetes, and clogged arteries, yet her body remained untouched by decay.

Her story is more than a scientific anomaly—it’s a cultural echo. In a time when death was feared and immortality sought, Lady Dai became a symbol of both. Her preservation challenges modern science, inspires historical reverence, and raises questions about ancient Chinese burial practices that remain unanswered.

Today, her body rests in the Hunan Provincial Museum, still drawing crowds, still defying time. She is not just a mummy—she is a mystery, a marvel, and a reminder that some lives leave a mark even after 2,000 years.