Just before sunrise on April 30, 1871, the desert near Camp Grant, Arizona, lay silent. Along the bank of Aravaipa Creek, dozens of Apache families slept beneath makeshift brush shelters. They believed they were finally safe. For months, the Aravaipa and Pinal Apache bands had sought peace. They had laid down weapons. They had accepted rations. They had remained close to the U.S. Army camp for protection. Among the families was a young girl remembered in oral tradition as Sech’ida, “The One Who Hears the Dawn.”

Her mother taught her to read the desert: how wind changes before sunrise, how cactus birds announce danger, how thornbushes form thick shelters where even riders cannot see. She had once touched a cluster of catclaw bushes when gathering firewood. Her mother gently tapped the thorns and said: “These are the desert’s fingers. If danger comes, they will hold you.” Sech’ida didn’t understand until that morning. Just before the sun crested the mountains, she woke to a sound that didn’t belong to the desert at all:

Footsteps.

Many.

Fast.

In moments, the camp exploded with gunfire. A combined group of Tucson militia, Mexican fighters, and Tohono O’odham warriors attacked the sleeping families. They believed killing Apache women and children would stop raids, a belief built on lies, fear, and political rage. The ambush was merciless. Mothers grabbed babies and ran toward the creek. Men tried to shield their families with nothing but their bodies. Children screamed as bullets tore through brush shelters. Some tried to swim across the creek but were shot as they climbed the opposite bank. Sech’ida ran toward the desert. Not toward the open ground but toward the thornbushes. She dove beneath the catclaw, its branches tearing into her arms. She pressed herself low against the sand as thorns wrapped over her like a cage. From inside the brambles, she saw everything: Women falling as they tried to reach their children. Infants thrown into the air.

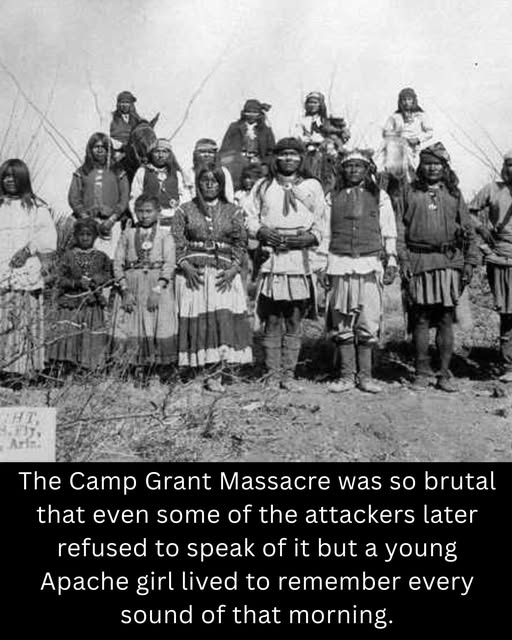

Fire spreading across shelters. The attackers laughing as they moved through the camp. Bodies lying along the water like fallen dolls. By noon, more than 140 Apache people, most of them women and children, were dead. Almost no adult men survived. Almost no children were left alive. When the attackers left, silence returned to the desert, the kind of silence that feels like the world holding its breath. Sech’ida crawled out from beneath the thorns, shaking, bleeding from scratches. The camp was gone. The creek ran red. Smoke drifted into a sky too bright for such horror. She walked alone until she found an older girl hiding in a mesquite thicket. Together, they followed the creek upstream, moving slowly, stopping at every sound. By nightfall, they reached Fort Grant and collapsed in exhaustion. Soldiers took them in, stunned by what had happened. Sech’ida lived into adulthood. She carried the memory of that morning all her life, the screams, the smoke, the thorns, and the way the land held her when no one else did. Her descendants later said she would pause beside catclaw bushes and touch their thorns gently, whispering: “The desert held me. It remembers.” The Camp Grant Massacre remains one of the worst atrocities ever committed against the Apache, yet it is rarely taught in American schools.