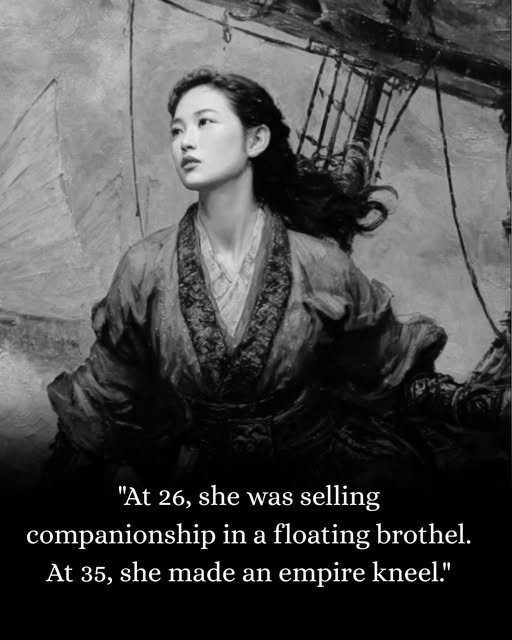

At 26, she was selling companionship in a floating brothel. At 35, she made an empire kneel.

In 1801, Shi Yang was invisible—one of thousands of women trapped in poverty along the Canton docks. The world had decided her story before she was born. She would live small, serve men, and disappear.

Then a pirate captain walked into the brothel.

Zheng Yi commanded the Red Flag Fleet, the most feared force on the South China Sea. Some say he proposed marriage. Others say he tried to take her by force. What matters is what happened next.

Shi Yang negotiated.

She would marry him—but only if she owned half of everything and controlled half his fleet. The pirate, accustomed to taking what he wanted, agreed to share power with a woman who owned nothing.

It may have been the most important business decision in pirate history.

Together, they built something unprecedented: a confederation of six fleets flying different colored flags, commanding 400 ships and 40,000 pirates. For scale, the legendary Blackbeard never controlled more than 4 ships and 300 men.

Then Zheng Yi died in 1807. And the woman the world tried to erase did something it never expected.

Within weeks, she had consolidated absolute power. She took her husband’s second-in-command as her new husband—a strategic alliance that secured the loyalty of his men. She imposed a code of laws so severe that seasoned criminals feared to break it. Desertion meant losing your ears. Disobeying orders meant death.

The code was brutal. But it created something unprecedented: discipline among chaos.

At her peak, the woman now known as Ching Shih commanded up to 1,800 ships and 80,000 pirates—a fleet larger than most national navies. Entire coastal regions paid her tribute. Those who refused faced annihilation.

In 1808, the Qing Dynasty set a trap for her. She sailed directly into it—and emerged victorious, leaving half the imperial navy in ruins. The Chinese commander took his own life in shame.

The empire tried again the next year, this time with British and Portuguese support. Three navies blockaded her fleet for three weeks with relentless cannon fire.

The pirates broke through.

But Ching Shih understood something crucial: even the most powerful empires have limits. Internal divisions were forming. A rival fleet commander had defected. Victory was no longer certain.

So she did something even more audacious than winning. She negotiated peace.

In 1810, she presented herself to Qing officials—not as a defeated criminal, but as an equal negotiating terms. She demanded full amnesty for her entire fleet, the right to keep her ships and wealth, and positions in the imperial navy for her men.

There was one problem: protocol required anyone accepting imperial mercy to kneel. Ching Shih refused.

The solution was brilliant. She agreed to formalize her marriage to Zhang Bao in front of the Qing official—and as part of the ceremony, they knelt to thank him for witnessing their union. Not in surrender. In gratitude.

Honor preserved. Empire satisfied.

The emperor who had spent years trying to destroy her accepted every term.

Ching Shih retired at 35 with her fortune intact. She opened businesses in Canton—a gambling house and, some sources suggest, the very brothel where her story began. But this time, she owned it.

She lived another 34 years, managing her wealth until her death in 1844 at age 69. She remains one of the only pirates in history to retire wealthy, powerful, and peacefully.

But the full story matters.

Her fleet didn’t just fight naval battles. They terrorized coastlines, massacred civilians, and trafficked captives. Power built on violence rarely comes clean.

Ching Shih wasn’t a hero in the traditional sense. She was something more complex: a woman who refused every limitation placed on her existence, who commanded where she was meant to obey, who negotiated where she was meant to surrender.

In a world designed to erase people like her, she made herself unforgettable.

The brothels of Canton produced countless forgotten women. The South China Sea claimed countless forgotten pirates.

But Ching Shih bent an empire. And her name survived.

Sometimes the most radical act isn’t being virtuous. It’s refusing to disappear.