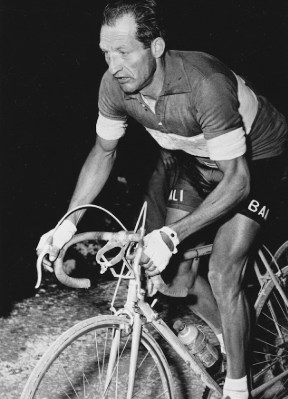

Italy, 1943. German forces had occupied the country after the government’s collapse. Jewish families who had lived in Italy for generations were now being hunted, rounded up, shipped to camps in sealed cattle cars. The countryside was a maze of military checkpoints. Roads bristled with armed soldiers. No one moved without papers. No one traveled without being searched. No one except Gino Bartali. At 29, Bartali was more than a cyclist. He was a national icon. He had won the Tour de France in 1938, dominating the world’s most grueling race. He had conquered the Giro d’Italia multiple times. His face appeared on newspapers across the country. Children wore his jersey. When he rode through town, crowds gathered to cheer. The soldiers at the checkpoints knew his face as well as they knew their own commanders. And Gino Bartali realized he possessed something more valuable than any medal: invisibility hiding in plain sight.

One day, a message arrived from Cardinal Elia Dalla Costa of Florence. The Cardinal was secretly coordinating a network to save Jewish families hiding in convents, monasteries, and private homes across Tuscany. They had documents, forged identity papers that could mean the difference between life and death. But they couldn’t transport them. Every courier they sent was stopped, searched, arrested. “We need someone the soldiers won’t search,” the Cardinal said. Bartali understood immediately. “I will go.” His plan was audacious in its simplicity. He would tell everyone he was training for the next big race. He would wear his racing jersey with his name emblazoned across the chest. He would ride the routes between Florence and Assisi, sometimes covering 250 miles in a single day, distances that seemed insane to anyone who didn’t know professional cycling. But before each ride, in the privacy of his home, he performed a different ritual. He would carefully unscrew the seat post and handlebars of his bicycle. Inside the hollow steel tubes of the frame, he would roll up photographs and forged documents: baptismal certificates, identity cards, ration books. Everything a Jewish family needed to become, on paper, Catholic Italians. Then he would reassemble everything, mount his bike, and ride toward the checkpoints.

When soldiers stopped him, and they did, he had his script ready. “Gino Bartali! The champion! Can we get a photograph?” He would smile, chat, sign autographs. And when they moved toward his bicycle, he would become urgent, protective. “Please, don’t touch the bike! Every component is perfectly calibrated. If you adjust anything, even slightly, it ruins the balance. I have to race in weeks!” The soldiers, starstruck and not wanting to damage the equipment of a national hero, would step back. They would wave him through. They never suspected that inside the frame of the bicycle they were admiring, hidden in millimeters of hollow steel, were documents that would save entire families. Bartali rode past machine guns. He rode past tanks. He rode past barbed wire and military convoys. He rode in rain, in summer heat, through exhaustion that had nothing to do with training and everything to do with fear. If the Nazis discovered even one forged paper, he would be executed on the roadside. His wife and children would likely be killed as well.

But he didn’t stop with courier runs. In his own home, in a concealed basement space, Bartali hid the Goldenberg family. Jewish refugees with nowhere else to go. Every day he brought them food. Every night he prayed they wouldn’t be discovered. Every morning he woke up and made the choice again: to risk everything. By the time the war ended in 1945, Bartali’s secret network had saved approximately 800 Jewish lives. Eight hundred parents, children, grandparents who survived because a cyclist used his fame as a weapon against tyranny. When liberation came, Bartali simply went back to racing. In 1948, at age 34, when most athletes had long since retired, he stunned the cycling world by winning the Tour de France again. Ten years after his first victory. The press swarmed him with questions. They wanted to know how he had trained during the war years. What had he been doing? He smiled and said nothing. For the next 52 years, Gino Bartali never spoke publicly about what he had done. When his son asked about rumors of wartime heroism, Bartali said: “Good is something you do, not something you talk about. Some medals are pinned to your soul, not to your jacket.” He died in May 2000, at age 85, still silent about his wartime actions.

Only after his death did his family discover the diaries, the letters, the documentation. Only then did the survivors come forward. Children and grandchildren of the families Bartali had saved began sharing their stories. A photograph here, a forged document there. Testimony from aging partisans who had worked alongside him. In 2013, thirteen years after his death, Israel’s Holocaust memorial Yad Vashem recognized Gino Bartali as Righteous Among the Nations, an honor given to non-Jews who risked their lives to save Jews during the Holocaust. The cycling champion who once stood on podiums holding trophies was finally acknowledged for the victories that truly mattered. Not the races he won, but the lives he saved. Not the medals pinned to his jacket, but the ones pinned to his soul. Gino Bartali proved something the world needs to remember: heroism isn’t always loud. Sometimes it’s a man on a bicycle, pedaling through enemy territory with documents hidden in hollow steel tubes, racing not for glory, but for humanity.