April 15, 1912. Nineteen-year-old Jeremiah Burke stood on the deck of the RMS Titanic as it tilted into the North Atlantic. Around him, lifeboats descended half-empty into the black water. The ship’s band played on. Desperate passengers clung to whatever hope they could find.

Jeremiah reached into his coat and pulled out a small glass bottle. His mother had pressed it into his hands just days before at the harbor in Queenstown, Ireland. A bottle of holy water. “Keep this with you,” she’d told him. “It will protect you.”

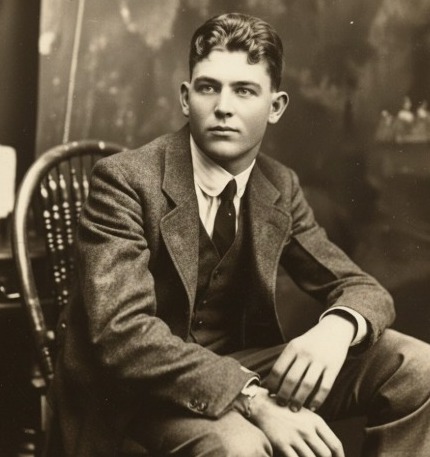

He was traveling to Boston with his cousin Nora Hegarty, chasing the same dream as millions of Irish emigrants before them. Two of his sisters had already made new lives in America, and they’d sent money for his passage. At 6 feet 2 inches tall, Jeremiah was a farm laborer with calloused hands and big hopes. He and Nora had imagined the streets of Charlestown, the jobs waiting for them, the family reunions.

Now, with freezing water rising and the bow plunging downward, that future was vanishing.

Jeremiah found a scrap of paper. His hands, perhaps shaking from cold or fear or both, scrawled a final message in pencil: “From Titanic, goodbye all, Burke of Glanmire, Cork.”

He folded the paper, pushed it into the bottle his mother had given him, and tied it shut with one of his own shoelaces. Then he hurled it as far as he could into the darkness.

Minutes later, the ocean claimed him. Jeremiah Burke and Nora Hegarty were among the 1,500 souls who perished that night. Their bodies were never recovered.

The bottle drifted.

Through storms and swells, across hundreds of miles of Atlantic currents, it traveled. Most messages in bottles sink within days. The paper dissolves. The glass shatters. The words disappear into the depths, unread and unknown.

But this bottle survived.

Thirteen months later, in the summer of 1913, a man walking his dog along the beach at Dunkettle discovered something unusual among the rocks and seaweed. A small bottle, sealed with a shoelace, with a piece of paper inside.

Dunkettle is just a few miles from Glanmire.

The finder brought the bottle to the local police, who delivered it to the Burke family home. When Kate Burke untied the shoelace and unrolled the note, she immediately recognized her son’s handwriting. She looked at the bottle—the same holy water bottle she had filled and given to Jeremiah as he left for America.

Her boy’s last words had come home.

The Burke family never sought publicity. They didn’t sell the artifact or seek attention. For nearly a hundred years, the bottle remained on the wall of the family home in White’s Cross, Cork. A private memorial. A reminder of the young man who never returned, and the life he should have lived.

Children grew up in that house knowing the story. Grandchildren and great-grandchildren learned about Uncle Jeremiah, the farm boy who dreamed of America, whose final act was reaching out through death to say goodbye.

In 2011, Jeremiah’s niece Mary Woods made a decision. She and her family agreed to donate the bottle to the Cobh Heritage Centre, where it would become part of the permanent Titanic exhibition.

“The note was in a frame in our old family home, and people came over the years to see it,” Mary explained. “But with the centenary coming up, we decided it would be good to hand it over. Now it will be on show for everyone.”

Today, visitors from across the world stand before a glass case at the Cobh Heritage Centre. Inside is a small bottle, tied with a bootlace, containing a faded note in pencil.

They can connect across more than a century to a teenager’s final moments. To the mother who gave him holy water for protection. To the impossible journey of a message that traveled hundreds of miles to land exactly where it needed to be.

Of the 2,240 people aboard the Titanic, most left behind only names on passenger lists and fading photographs. But Jeremiah Burke left something more.

He left proof that even in our darkest hours, we reach for connection. That love can cross oceans and survive death itself. That a simple act—a message sealed in a bottle and thrown into the void—can touch hearts more than a hundred years later.

His bottle made it home.

And because it did, Jeremiah Burke’s name, his story, and his final act of love will never be forgotten.