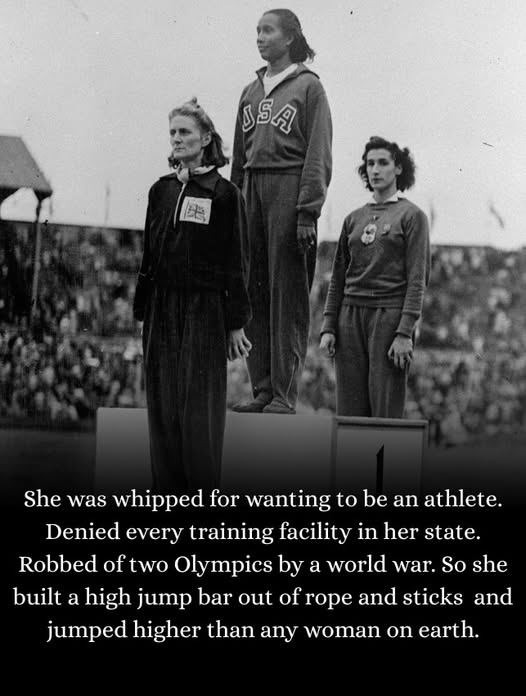

On a rainy August afternoon in 1948, Alice Coachman stood before 83,000 spectators at London’s Wembley Stadium. She was 24 years old, competing with a rod surgically inserted into her back to manage a painful injury doctors had told her would keep her from the Games. No American woman had won a single gold medal at these Olympics.

She cleared 5 feet, 6 and 1/8 inches on her first try. A new Olympic record.

King George VI placed the gold medal around her neck.

Nothing about getting there had been easy.

Alice Coachman was born on November 9, 1923, in Albany, Georgia — the fifth of Fred and Evelyn Coachman’s ten children. Her family was poor. Young Alice supplemented their income picking cotton, supplying corn to local mills, and selling plums and pecans. But the girl could run, and she could jump — higher than anyone.

The problem was that she was Black, and female, in the segregated South. Public athletic facilities were whites-only. Organized sports programs for girls barely existed. Her father wanted her to sit on the porch and look “dainty.” When she kept running, he whipped her for it.

It didn’t stop her.

She ran barefoot on dirt roads. She built a high jump crossbar out of rope and sticks. And she found allies: her fifth-grade teacher, Cora Bailey, and her aunt, Carrie Spry, who defended Alice’s athletic dreams against her parents’ fears. A high school coach named Harry Lash saw her talent and nurtured it. In 1939, the Tuskegee Institute offered her a scholarship.

Before Alice Coachman ever sat in a Tuskegee classroom, she broke the national high school and college high jump records — barefoot.

For the next nine years, she won every single national high jump championship: ten in a row, a streak never matched. She won 26 national titles across high jump, sprints, and relay. She was a three-time conference basketball champion. Sportswriters called her the “Tuskegee Flash.”

She should have been an Olympic champion two or three times over. But World War II cancelled the 1940 and 1944 Games — the years she was at her athletic peak. “Had she competed in those canceled Olympics,” sportswriter Eric Williams later wrote, “we would probably be talking about her as the No. 1 female athlete of all time.”

By 1948, she was 24 — past her prime, nursing a back injury, and finally getting her one chance. At the Olympic trials, she shattered the existing American record despite the pain. In London, her nearest rival — Britain’s Dorothy Tyler — matched her historic jump, but only on her second attempt. Coachman did it on her first. Gold.

She became the first Black woman from any country in the world to win an Olympic gold medal. She was the only American woman to win gold at those Games.

When she came home, America celebrated — and segregated. Count Basie threw her a party. President Truman congratulated her at the White House. Georgia gave her a 175-mile motorcade from Atlanta to Albany. But in the Albany auditorium where her hometown honored her, Black people and white people were forced to sit separately. The white mayor sat on the stage beside her but refused to shake her hand. She had to leave her own celebration through a side door.

“To come back home to your own country, your own state and your own city, and you can’t get a handshake from the mayor?” she recalled. “Wasn’t a good feeling.”

She retired from competition after those Games, finished her degree at Albany State College, and became a teacher. In 1952, Coca-Cola signed her as a spokesperson — making her the first Black female athlete to endorse an international brand. She was inducted into nine Halls of Fame, including the U.S. Olympic Hall of Fame, and was honored at the 1996 Atlanta Olympics as one of the 100 greatest Olympic athletes in history.

Alice Coachman died on July 14, 2014, at the age of 90.

But she never doubted what her gold medal meant.

“I made a difference among the Blacks, being one of the leaders,” she told The New York Times in 1996. “If I had gone to the Games and failed, there wouldn’t be anyone to follow in my footsteps. It encouraged the rest of the women to work harder and fight harder.”

She opened a gate that would never close. Wilma Rudolph walked through it. Evelyn Ashford walked through it. Florence Griffith Joyner and Jackie Joyner-Kersee walked through it. Every Black woman who has ever stepped onto an Olympic track owes something to a barefoot girl from Albany, Georgia, who built her own crossbar from rope and sticks.