On the morning of July 1, 1863, Tillie Pierce Alleman woke in Gettysburg to a sound she had never heard before. Dull at first. Distant. Like thunder that refused to fade. Cannon fire rolled across the Pennsylvania countryside, and with it came the realization every family in town had feared but prayed would never arrive. War was no longer something happening somewhere else.

It was coming through their streets.

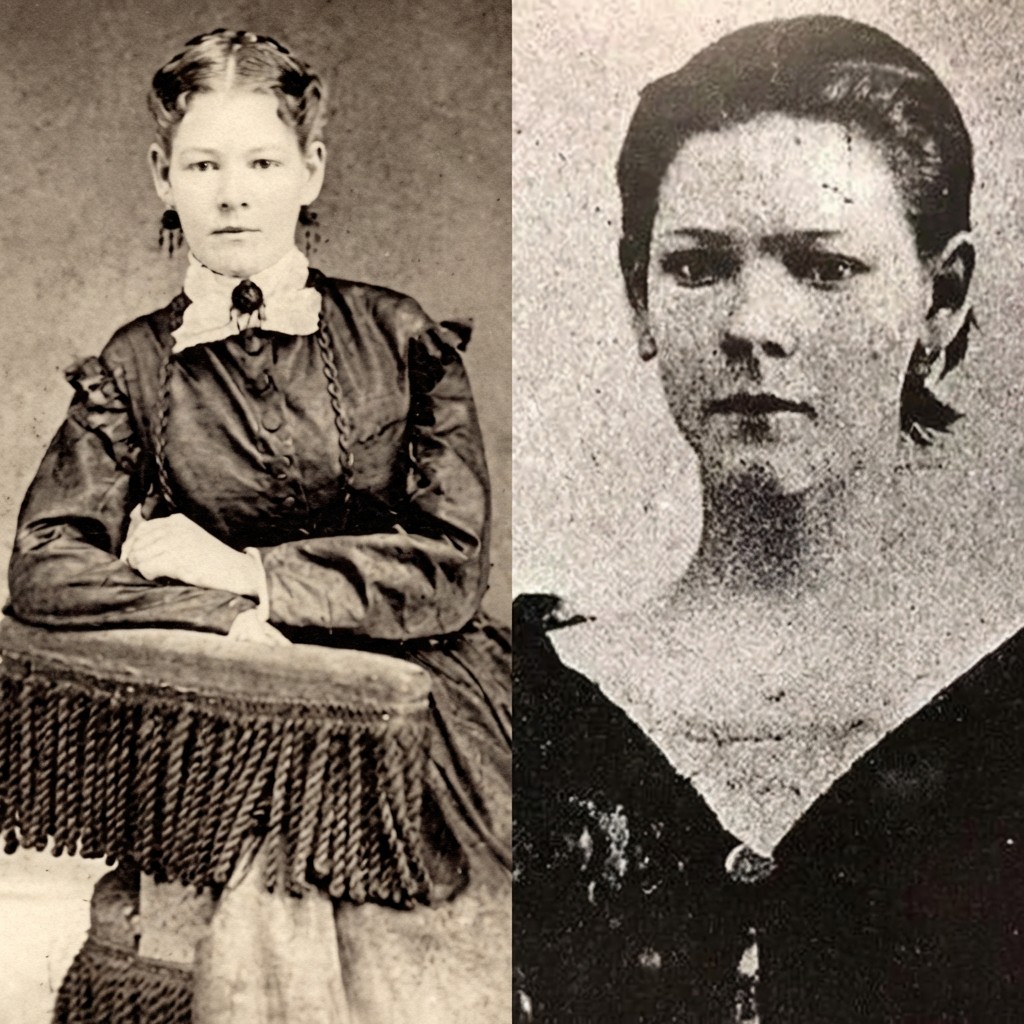

Tillie was fifteen years old. A girl whose life had been measured in school lessons, chores, neighbors’ faces. By afternoon, Union and Confederate forces had collided just outside town, and the fighting spilled inward like a flood. Soldiers ran bleeding past houses. Horses screamed. Shells struck buildings. Families fled to cellars. Gettysburg, peaceful that morning, became a battlefield by nightfall.

Her family made a desperate choice. They sent Tillie away from town to the Weickert farm, two miles south, believing distance might equal safety. The farm sat along the Taneytown Road, near the Round Tops, but to them it was simply farther from the streets now filled with terror.

They could not have known it was a mistake.

When Tillie arrived, the fields were still quiet. But by the next day, the Union Army poured in. Artillery wagons churned the earth. Ammunition trains stretched across the land. Thousands of soldiers marched past the farmhouse, boots beating time into the soil. Boys barely older than Tillie. Men the age of her father. Faces set with fear, courage, resignation, all at once.

She watched them move toward the hills where, before sunset, many would fall.

She could not just stand there.

Tillie picked up a bucket and began carrying water. Back and forth she walked, offering it to soldiers as they passed. Some thanked her quickly and moved on. Some joked, forcing cheer into their voices. Others said nothing at all, already preparing themselves for what waited beyond the ridgeline.

Then the wounded came.

The Weickert farm became a field hospital almost instantly, as did every building near the fighting. Men were laid on porches, on grass, on bare earth. Blood soaked the ground. The air filled with the smell of iron and smoke. Surgeons worked without pause, sawing through shattered limbs because there was no time and no anesthesia enough for the numbers arriving.

Amputated arms and legs were stacked outside like cordwood.

Tillie had never seen death before. Now it surrounded her.

She was fifteen years old, and she did not run.

She carried water to men who could no longer lift their heads. She held hands while saws cut through bone and screams tore into the air. She wrote letters for soldiers whose fingers would never hold a pen again. She listened as boys whispered final messages meant for mothers and wives who would never hear them spoken aloud.

One man, shot through the body and fading fast, asked her to sing.

So she did.

In the middle of a farm turned into a place of unbearable suffering, a fifteen year old girl sang hymns to a dying stranger, her voice steady because it had to be, because it was the only comfort she could give as life slipped away beneath her hands.

For three days, July 1st, 2nd, and 3rd, the Battle of Gettysburg raged. More than fifty thousand men would be killed, wounded, or missing. From the farm, Tillie could see parts of it unfold. The thunder of artillery. The desperate fighting near Little Round Top. The flood of shattered bodies after Pickett’s Charge, when the fields seemed to empty of hope entirely.

When the guns finally fell silent, the suffering did not stop. Gettysburg became one vast hospital. Men died slowly from infection, shock, wounds no one yet knew how to treat. The war did not end with the battle. It lingered in moans, in fevers, in graves dug too quickly.

Tillie eventually returned home.

But the girl who came back was not the girl who had left.

She had seen war without the veil of glory. She had seen it at arm’s length. Broken bodies. Endless screaming. Young men calling for their mothers as life drained out of them. She understood something that textbooks and speeches often hide. That war, up close, is not heroic. It is intimate. It is tragic. It is unbearable.

Many would have tried to forget.

Tillie chose memory.

In 1889, twenty six years later, she published her account, At Gettysburg: What a Girl Saw and Heard of the Battle. It remains one of the most vivid civilian records of the battle ever written, precisely because it refuses romance. She wrote about amputations without anesthesia. About piles of limbs. About singing to dying boys. About water offered and gratitude returned with last breaths.

She wrote because forgetting felt like another kind of death.

Tillie Pierce Alleman lived until 1914. She spent her life honoring the men she had helped, refusing to allow their suffering to be wrapped in myth or patriotism alone. She knew that history needs witnesses who tell the truth, not the version that makes future wars easier to start.

She did not carry a rifle.

She carried a bucket of water.

She did not choose the battlefield.

She refused to look away once she was there.

At fifteen years old, Tillie Pierce became a witness to the bloodiest battle of the American Civil War. Her courage was not loud. It did not wear a uniform. It looked like hands steady enough to hold another’s pain and a voice brave enough to sing while the world fell apart.

Heroism does not always march.

Sometimes it kneels beside the wounded and stays.

And because Tillie wrote it down, the world cannot pretend it did not happen.