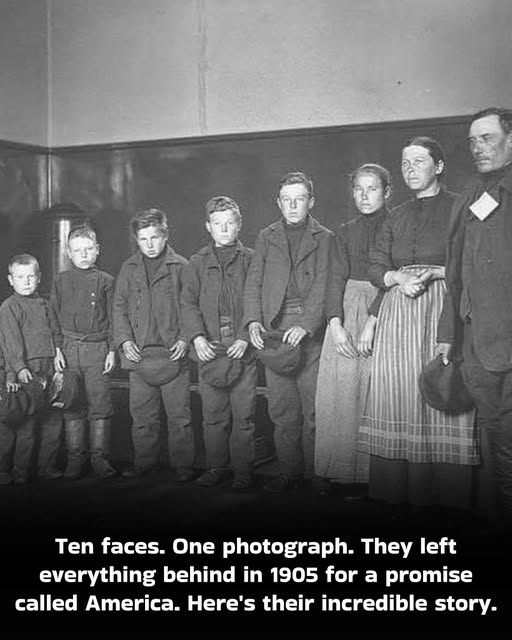

On May 9, 1905, a weary family of ten stood before a camera at Ellis Island, New York. The photographer was Augustus Sherman, a clerk who spent decades documenting the remarkable faces of immigration. He captured thousands of images, but this one would become iconic.

The caption typed onto the photograph reads: “Jakob Mittelstadt and family, Russian German, ex SS Pretoria, May 9, 1905. Admitted to go to Kullen, N.D.”

Look closely at this photograph. You see a father, a mother, seven sons, and one daughter. Their faces tell a story that words cannot fully capture. The parents show the weathered determination of people who have already survived more than most could imagine. The children’s expressions range from uncertainty to quiet hope. Together, they represent one family’s leap into the unknown.

But who were they? Where did they come from? And what became of them?

The Mittelstadt family came from a small village called Klöstitz, located in what was then the Bessarabian Governorate of the Russian Empire. Today, that village is known as Vesela Dolyna in Ukraine, situated less than 80 miles from Chișinău, the capital of modern Moldova. They were part of a fascinating group known as “Germans from Russia” whose story stretches back more than a century before this photograph was taken.

In 1763, Catherine the Great, Empress of Russia, issued a historic manifesto that would change the lives of hundreds of thousands of people across generations. Born a German princess herself, Catherine understood something her Russian predecessors had not: the vast, fertile lands of her empire lay largely uncultivated and undefended. She needed skilled farmers to work the soil and settlers to create a buffer against nomadic tribes threatening her borders.

Her manifesto offered German-speaking families an extraordinary deal. Come to Russia, she promised, and you will receive free land, tax exemptions for thirty years, freedom to practice your religion without interference, exemption from military service, the right to govern your own communities, and travel expenses paid by the Russian crown. For families struggling in the war-ravaged German states after the devastating Seven Years’ War, this sounded like paradise.

Tens of thousands answered Catherine’s call. Some settled along the Volga River near Saratov. Others, like the ancestors of the Mittelstadt family, settled in Bessarabia and the Black Sea region, areas Russia had acquired from the Ottoman Empire. They built villages that looked remarkably like the ones they had left in Germany, complete with Lutheran churches, German schools, and familiar customs. For generations, they maintained their language, their traditions, and their identity.

Life was good for these German colonists for nearly a century. They prospered as farmers, turning the Russian steppes into productive agricultural land. They kept to themselves, married within their communities, and preserved their German heritage while technically being subjects of the Russian Tsar.

Then everything changed.

In 1871, Tsar Alexander II revoked the special privileges that Catherine had promised. The colonists lost their tax exemptions and their exemption from military service. For the Mennonites and other pacifist groups, this was devastating. But even for Lutheran families like the Mittelstadts, the loss of their unique status was troubling. They were now just like any other Russian peasant, subject to the same laws, the same taxes, and the same military conscription.

Economic conditions worsened. A series of famines swept through the region. Political turmoil mounted. By the early 1900s, Russia was heading toward the catastrophic Russo-Japanese War and the Revolution of 1905. The German colonists who had once been welcomed guests now faced growing hostility from a government and populace that viewed them with suspicion.

The same spirit of adventure that had led their ancestors to leave Germany for Russia now compelled a new generation to seek opportunity elsewhere. This time, the destination was America.

When the Mittelstadt family arrived at Ellis Island after their long voyage aboard the SS Pretoria, they were not simply waved through. Records show they were detained and held for Special Inquiry, undergoing two hearings over eight days before finally being admitted. The immigration officials needed to be satisfied that this family of ten would not become a burden on the American public.

The destination listed on their paperwork was “Kullen, N.D.” This appears to have been a misspelling or mishearing of Kulm, a small town in south-central North Dakota that had been founded just thirteen years earlier, in 1892. According to descendants, the family actually settled on a farm closer to the town of Forbes.

They had chosen wisely, even if they didn’t fully realize it at the time.

North Dakota’s semi-arid plains were remarkably similar to the steppes they had left behind in Bessarabia. The climate, the soil, the endless horizons, all reminded them of home. More importantly, they already knew how to farm this kind of land. They understood wheat cultivation in dry conditions. They knew how to build sturdy houses from available materials. They possessed generations of hard-won agricultural knowledge perfectly suited to their new environment.

The Mittelstadts were far from alone. Between 1870 and 1915, thousands of Germans from Russia immigrated to North Dakota, drawn by the promise of cheap and nearly limitless land offered through the Homestead Act. By 1910, approximately 60,000 ethnic Germans from Russia called North Dakota home. They became the largest immigrant group in the state, transforming the landscape with their farms and filling entire counties with their communities.

They brought more than farming skills. They brought their language, their customs, their distinctive black wedding dresses, their hearty cuisine, and their deep Lutheran faith. They established German-language newspapers, built churches that still stand today, and created communities that maintained their identity well into the twentieth century.

The photograph taken that day in 1905 eventually found its way into Augustus Sherman’s collection of Ellis Island portraits. For decades, it remained one image among thousands, its subjects anonymous faces in the great tide of immigration.

Then came a remarkable discovery.

In 1991, an elderly woman named Eldora Klose visited Ellis Island with her husband Elmer. They had traveled from Jamestown, North Dakota, to see their son in New York. Despite a broken ankle that forced Eldora to use a wheelchair, she insisted on visiting the immigration museum where she knew her ancestors had passed through decades before.

As they moved through an exhibit of Augustus Sherman’s photographs, her husband suddenly exclaimed. There, in a frame on the wall, was the Mittelstadt family portrait.

Eldora recognized one of the small boys immediately. The second youngest, standing second from the left in the photograph, was her father, Benjamin Mittelstadt. He had been just a child when Sherman’s camera captured that moment, standing with his parents and siblings on the threshold of a new life.

Benjamin grew up on that North Dakota farm, married Marie Presler in 1929, and raised his own family. He moved from Jud to Edgeley to LaMoure, finally retiring in Jamestown in 1963, where he died that same year. His wife Marie, at the time of a 2002 newspaper article about the photograph’s discovery, was still living in Jamestown at age 93.

The family that faced such uncertainty in 1905 had not only survived but thrived. Their descendants spread across North Dakota and beyond, becoming farmers, teachers, businesspeople, and community leaders. The promise that had drawn their ancestors first to Russia and then to America had been fulfilled across the generations.

When we look at this photograph today, we see more than ten immigrants in their traveling clothes. We see courage in the face of uncertainty. We see the determination to build a better life for children not yet born. We see a family that left behind everything familiar for a chance at something new.

The Mittelstadt family arrived just before turbulent times would sweep across both their old home and their new one. Russia would soon erupt in revolution. World War I would bring suspicion and discrimination against German-Americans, even those whose families had not lived in Germany for generations. The influenza pandemic, the Great Depression, and another world war would test the resilience of every family.

But they had already proven their resilience. Their ancestors had left Germany for Russia when Catherine called. They had left Russia for America when opportunity beckoned. Adaptation was in their blood.

Today, nearly half of North Dakota’s population traces its ancestry to these Germans from Russia. Their legacy lives in the farmland they cultivated, the communities they built, and the families they raised across generations.

One photograph. Ten faces frozen in a single moment. And behind them, a story that spans continents and centuries, from a German princess’s ambitious manifesto to a North Dakota grandmother discovering her father’s face on a museum wall.

The Mittelstadt family came to America seeking a better life. They found it.