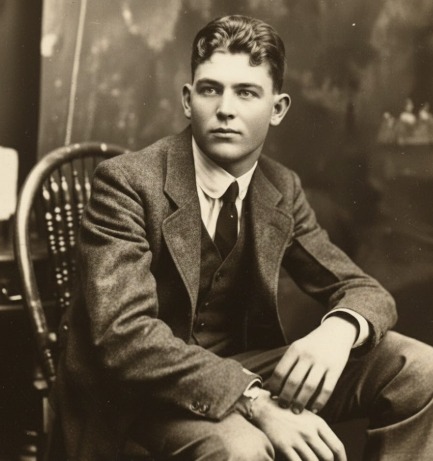

April 15, 1912. The RMS Titanic was sinking into the North Atlantic, and 19-year-old Jeremiah Burke from Glanmire, County Cork, knew he would not survive. Around him, chaos erupted. Lifeboats descended half-empty. The ship’s band played on. Desperate passengers searched for any hope of rescue.

Jeremiah reached into his coat and pulled out a small glass bottle. His mother had given it to him before he left Ireland—a holy water bottle to protect him on his journey to America. He was traveling to Boston with his cousin Nora Hegarty to reunite with family who had emigrated years earlier. They had dreamed of new beginnings. Of opportunity. Of the life waiting for them across the ocean.

Now that dream was ending in darkness and ice.

With the ship tilting beneath his feet and the frigid water rising, Jeremiah found a scrap of paper. In what would become his final act, he scrawled a message: “From Titanic, goodbye all, Burke of Glanmire, Cork.”

He sealed the note inside the bottle, tied one of his bootlaces around it, and hurled it into the black Atlantic waters. Then the ocean claimed him. He was among the 1,500 souls who perished that night. Nora died beside him.

The bottle drifted. Through storms and currents, across hundreds of miles of open ocean, it traveled. Most messages cast into the sea are never found. They sink or shatter or drift endlessly until the paper dissolves and the words disappear forever.

But not this one.

Nearly a year later, in 1913, a bottle washed ashore at Dunkettle, just a few miles from the Burke family home. Someone walking the beach discovered it among the rocks and seaweed. When they untied the bootlace and read the note inside, they realized what they held.

Jeremiah’s final words had come home.

The Burke family kept the bottle for nearly a century. It was not displayed publicly or used for fame. It remained a private relic of grief, a tangible connection to a young man who never returned, a reminder of the life he should have lived. Generations grew up knowing the story. Knowing that Jeremiah’s last act had been to reach out across death itself to say goodbye.

In 2011, Jeremiah’s niece Mary Woods made a decision. She donated the bottle to the Cobh Heritage Centre, where it became part of the permanent Titanic exhibition. Now visitors from around the world can see it. The small glass bottle. The faded paper. The bootlace still wrapped around it.

They can stand before it and connect across more than a century to a teenager’s final moments. To his love for his family. To his hope that somehow, against all odds, his words would reach them.

The Titanic carried approximately 2,240 people. Most left nothing behind but names on a manifest. But Jeremiah Burke left something more. He left proof that even in our darkest moments, we reach for connection. That love persists beyond death. That a simple message can travel through time and touch hearts a hundred years later.

His bottle made it home. And in doing so, it ensured that Jeremiah Burke would never truly be forgotten.