Ann was born in 1898 in Alabama. Her great-grandmother had been enslaved. But she learned to sew—and that skill became freedom. Her grandmother Georgia designed gowns for the plantation mistress. When she gained her freedom, she had a business waiting.

Three generations. Grandmother to mother to daughter. All masters of needle and thread.

In 1914, tragedy struck. Ann’s mother died suddenly. Ann was just 16. But clients were waiting. Orders needed filling. So she stepped up—and discovered she wasn’t just good. She was extraordinary.

Ann’s specialty was fabric flowers. Three-dimensional silk blooms so lifelike you’d swear they were real. She could create entire gardens on a gown. Her work wasn’t fashion. It was art.

In 1918, she enrolled in design school in New York. As one of the only Black students, she was segregated. Forced to work alone in a separate room. But Ann didn’t quit. When she graduated, she was ready.

By the 1920s, Ann Lowe dressed America’s elite. The Rockefellers. The Roosevelts. The Du Ponts. In 1947, Olivia de Havilland wore an Ann Lowe gown when she won her Oscar. The dress was unforgettable. But Ann’s name wasn’t on it.

Her clients loved her work. They just wouldn’t credit her. Because admitting a Black woman designed their gowns? That was too much for 1940s America.

Then came 1953. Janet Auchincloss wanted Ann to design a wedding dress for her daughter, Jacqueline Bouvier. Who was marrying Senator John F. Kennedy.

Ann created a masterpiece. Fifty yards of ivory silk taffeta. Portrait neckline. Fitted bodice with interwoven bands of tucking. A skirt embellished with tiny wax flowers. Eight weeks of meticulous work.

Ten days before the wedding, disaster struck. A flood tore through her studio. The wedding dress—ruined. Nine bridesmaids’ dresses—destroyed. Eight weeks of work—gone.

Ann didn’t panic. She didn’t call to explain. She just bought new fabric and got to work. For ten days straight, she and her team rebuilt everything by hand. From memory. She never told the Kennedy family what happened. Instead of making a $700 profit, she lost $2,200. But the dresses were perfect.

On September 12, 1953, Ann arrived at the Auchincloss estate in Newport to deliver the gowns. When she reached the door, a staff member stopped her.

“You need to go around back. Use the service entrance.”

Ann stood there holding the most important dress she’d ever made. And they wanted her to enter like a servant.

She looked at them and said: “If I can’t come in the front door, I’ll take these dresses back to New York.”

There was a wedding in a few hours. The bride needed her dress. There was no time to argue.

Ann walked through the front door.

The wedding was spectacular. Over 1,200 guests. Jacqueline looked stunning. Her dress was photographed from every angle. Featured on the cover of The New York Times. Talked about in every newspaper.

But no one mentioned Ann Lowe. Not one article credited the designer. The New York Times called it the work of “a New York dressmaker.” No name. No recognition.

Years later, when Jacqueline was First Lady, an article called her wedding dress the work of “a colored woman dressmaker, not the haute couture.”

Ann wrote to Mrs. Kennedy’s press secretary: “I would prefer to be referred to as a ‘noted negro designer’ which in every sense I am.” They apologized. The magazine never issued a correction.

Ann continued working. She opened a boutique on Madison Avenue—the first Black woman to have a couture salon in that prestigious neighborhood. But she was always undervalued. Clients would talk her into lowering prices. She poured everything into her work and got back almost nothing.

Then the losses came. In 1958, her son died in a car crash. In 1962, she lost an eye to glaucoma. In 1963, she declared bankruptcy. The IRS came after her. She lost her salon. Everything—gone.

But then something happened. Her debts were mysteriously paid off by an anonymous donor. Rumor had it: Jacqueline Kennedy. No one ever confirmed it. But Ann’s taxes were cleared. And she kept working.

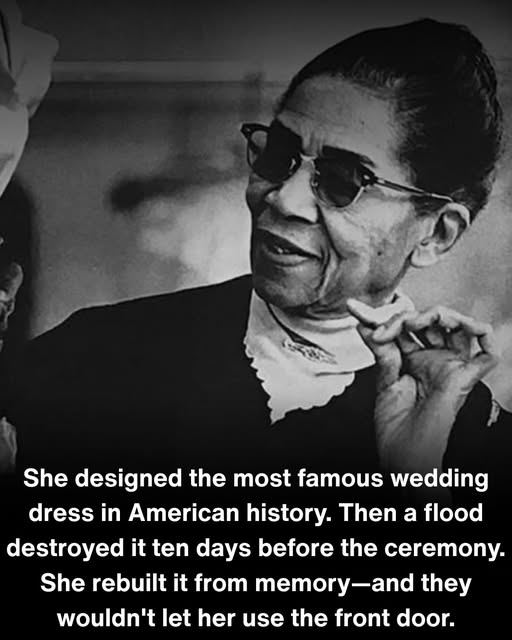

By the 1960s, magazines called her “society’s best-kept secret” and “The Dean of American Designers.” On The Mike Douglas Show in 1965, she said: “My greatest motivation is to prove that a Negro can become a major dress designer.”

But by then, her sight was failing. In 1972, she retired—blind and penniless. Ann Lowe died on February 25, 1981, at age 82. She had spent her entire life creating beauty for people who wouldn’t say her name.

For decades, her name was erased from history. Most people didn’t know a Black woman designed the most iconic wedding dress in America.

But in recent years, that’s changing. In 2022, the Metropolitan Museum of Art featured her work. In 2023, Winterthur Museum opened “Ann Lowe: American Couturier”—a major retrospective. The University of Delaware spent six months recreating Jackie Kennedy’s wedding dress, studying every stitch, bringing Ann’s vision back to life.

And now, people are finally learning her name.

Ann Lowe. Not “a colored woman dressmaker.” Not “society’s best-kept secret.”

Ann Lowe. A visionary. A pioneer. An artist.

She was the great-granddaughter of an enslaved woman. She took over a business at 16. She was segregated in design school. She dressed the wealthiest families in America. She designed one of the most photographed wedding dresses in history. She recreated it in ten days after a flood. She refused the service entrance. She lost her son, her eye, her business, her sight. She died penniless.

But her legacy endures.

Today, her gowns are in the Smithsonian. The Metropolitan Museum of Art. The Kennedy Presidential Library. Her fabric flowers are studied by fashion historians. Her techniques are taught in design schools.

Ann Cole Lowe. December 14, 1898 – February 25, 1981. American couturier. The first Black woman to achieve wide recognition in American fashion. Designer of Jacqueline Kennedy’s wedding dress.

She deserved better. She deserved credit while she was alive. She deserved to be celebrated.

But even though the world tried to erase her, her work remains.

And now, finally, we remember.