The official war was over, but militia patrols continued attacking Indigenous families, Nisqually, Puyallup, and others, claiming they were “preventing uprisings.”

Most of those killed in these raids were not warriors.

They were families trying to rebuild their homes.

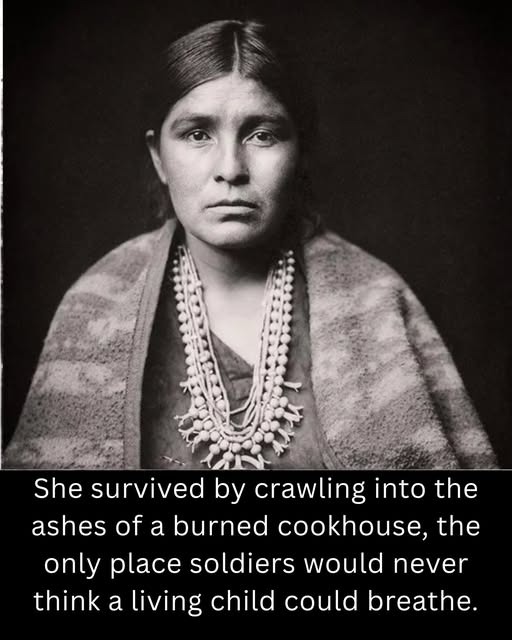

In a small winter village near the mouth of the Nisqually River lived a girl remembered in oral tradition as Talʼsaya, “Little Ember.”

Her grandmother often pointed to the remnants of a cookhouse that had burned in a storm years earlier: a shallow ash pit, charred cedar beams, cold earth.

She told her:

“Fire remembers us.

If danger comes, the cold ashes will hold you.”

Talʼsaya never understood why.

Until the morning the soldiers arrived.

Just after dawn, horses approached the village. Before anyone could speak or raise a hand, rifle fire tore through the lodges.

Women grabbed children. Elders tried to step forward to talk.

No one was allowed a word.

Smokehouses were set on fire.

Plank lodges were smashed apart.

Families ran in every direction.

Talʼsaya’s mother pushed her toward the old cookhouse pit.

“Go to the ashes.

Do not move.

Do not breathe loudly.”

Talʼsaya slid into the pit and pulled a blackened board over herself.

Ash coated her face.

Her heartbeat echoed in her ears.

From beneath the plank she saw:

Boots.

Falling embers.

Shadows of rifles crossing over her.

She heard everything:

Women begging.

Children screaming.

Soldiers shouting.

The cracking of burning cedar.

Ash drifted into her eyes.

Cold earth pressed against her ribs.

But she did not move.

Hours passed before the gunfire stopped.

When Talʼsaya crawled out, the village was silent.

Burned cedar.

Collapsed roofs.

Scattered baskets and blankets.

Smoke rising where food once dried.

Most of her family was gone.

She followed a narrow marsh path until she found survivors hiding in cattails, mostly women and children who had fled into the reeds. They carried her with them as they walked north for days, avoiding militia patrols.

She lived long into old age.

And when her grandchildren asked how she survived, she would kneel beside a fire, take a pinch of ash between her fingers, and say:

“The fire kept my breath.

So I must keep the memory.”

This attack was one of several militia reprisals documented in Washington Territory reports, events rarely taught today, remembered only because survivors protected the truth when official records refused to.