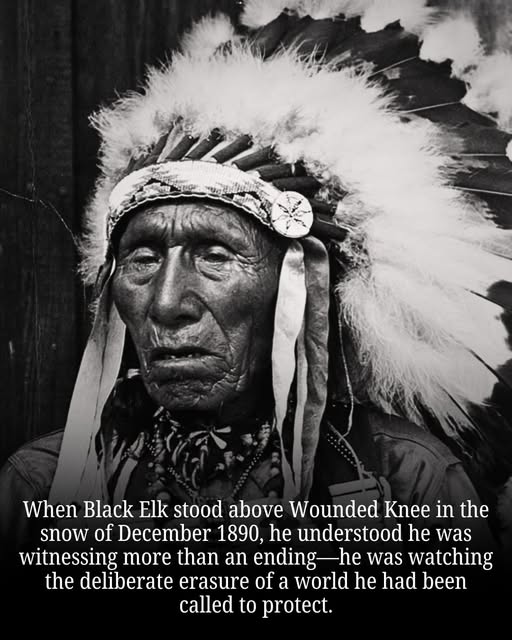

When Black Elk stood above Wounded Knee in the snow of December 1890, he understood he was witnessing more than an ending—he was watching the deliberate erasure of a world he had been called to protect.

Born in 1863 into the Oglala Lakota, Black Elk received a vision as a child that would define his life. He saw horses dancing across the sky, thunder beings moving through clouds, and a sacred tree meant to shelter all peoples. The elders who heard his vision understood it as a calling. He would carry responsibility for his people through the darkness that was coming.

What came was the systematic dismantling of everything his vision had shown him.

At thirteen, Black Elk witnessed the aftermath of Little Bighorn, where Lakota and Cheyenne warriors defeated George Armstrong Custer’s forces in 1876. The victory felt like vindication. It lasted mere months. Retaliation arrived with crushing force. Land was seized. Treaties signed in good faith were torn apart openly. Reservations became prisons dressed as protection.

By the late 1880s, desperation had taken root so deeply that many Lakota turned to the Ghost Dance—a spiritual movement promising renewal and the disappearance of the forces destroying them. U.S. authorities saw not prayer but rebellion. They responded with soldiers.

On December 29, 1890, at Wounded Knee Creek, those soldiers killed more than 250 Lakota men, women, and children. Black Elk was there. He carried the wounded through frozen ground. He lifted bodies that would never rise again. He watched snow turn red with blood and then fall silent under more snow, covering everything as if it had never happened.

Later, he would say that the nation’s sacred hoop—the circle that held his people together—was broken there and scattered beyond repair.

But Black Elk did not break with it.

Survival demanded adaptation. He converted to Catholicism and worked as a catechist, teaching the faith of those who had conquered his people. Outsiders would later argue whether this was compromise or betrayal. Black Elk never saw it as either. He understood that survival sometimes requires speaking in the language of power while keeping the old language alive in quieter places.

In the 1930s, he shared his life with writer John G. Neihardt, and together they created Black Elk Speaks. The book brought Lakota worldview to millions, but it also filtered his words through a non-Native perspective. Parts were simplified. Some meanings were lost in translation. The world listened, but not always to what Black Elk actually said.

That tension lives in his legacy still.

Black Elk was not a prophet trying to predict the future or resurrect the past. He was a witness determined to document what was taken and what remained. He did not speak to preserve some imagined purity. He spoke to preserve memory itself—because he understood that stories carry weight when land and sovereignty have been stripped away.

Black Elk did not fail to save his world. That was never within any one person’s power.

What he did was refuse to let its destruction be forgotten or distorted. His vision was never about reversing history. It was about ensuring that even in defeat, truth could survive and be transmitted forward.

When Black Elk said the sacred hoop was broken, he was not abandoning hope.

He was placing it carefully into the hands of anyone willing to remember what was done, who did it, and why forgetting would complete the work that violence had started. He understood that bearing witness is itself an act of resistance—and that the stories we refuse to let die become the seeds of what might still grow.