The air hung thick with the smell of wet earth and livestock, a familiar perfume to Graeme. His hands, gnarled and powerful, moved with a practiced grace that belied their rough exterior. Today, he was at the McGregor farm, a sprawling operation nestled deep in the undulating hills of the countryside. He’d been trimming hooves for over twenty years, a life lived on the edge of animal unpredictability and the ceaseless grind of rural industry. Each day was a symphony of precision and brute force, a dance between man, beast, and the ever-present threat of injury.

He spoke to the animals in low, soothing tones, a language understood universally by those with cloven hooves and a wary eye. “Easy now, big girl,” he murmured, stroking the flank of a Holstein heifer named Betsy, whose left hind had developed a nasty abscess. The hydraulic chute hummed, lifting her foot to a manageable height. Graeme’s eyes, keen and focused, scanned the hoof, already seeing the problem, the solution. He selected his grinder, a buzzing disc of steel, and began the meticulous work, paring away the diseased tissue, shaping the healthy horn. The dust flew, fine and acrid, mixing with the sweat beading on his brow.

He loved this work, the quiet satisfaction of alleviating pain, of seeing an animal walk freely again. But it was a love often accompanied by a razor’s edge of danger.

The incident came without warning, as they always did. It was a Tuesday, late autumn, at old man Henderson’s place. A young Friesian bull, still full of unbridled energy despite his burgeoning size, was proving difficult. He’d been in and out of the chute a dozen times already, his powerful shoulders shuddering with suppressed rage. Graeme had managed three hooves, each a battle of wills. It was the last one, the right fore, that sealed his fate.

He’d just finished paring away a stubborn piece of gravel that had burrowed deep into the sole. A simple, routine fix. He was lowering the foot, his focus entirely on the careful release, when the bull—without a sound, without a tremor—dropped his full weight, then snapped his head down, a lightning-fast movement Graeme had no time to anticipate.

A sharp, searing pain exploded across his face.

The world went white, then black, then burst into a kaleidoscope of sickening reds and yellows. He stumbled back, a scream catching in his throat, his hands flying to his face. The bull, seemingly unaware of the havoc it had wreaked, simply blinked, a lazy, bovine gaze.

Old man Henderson, who’d been holding the gate, dropped his jaw. “Graeme! Oh, good Lord, Graeme!”

Graeme felt a warmth gushing over his hands, slick and metallic. He pulled them away, saw the crimson, saw the deep, jagged tear above his left eye, running down towards his temple. A piece of the bull’s horn, sharp as a chisel, had caught him. It was deep. Too deep.

The farm suddenly dissolved into a chaotic swirl. Voices, urgent and distant. Hands, pulling him, guiding him. The sting of antiseptic, the blinding glare of emergency room lights. And then, the meticulous, horrifying count from the kind-faced nurse: “One, two, three… seventy-three stitches, Graeme. Right across your face.”

Seventy-three. Each one a tiny, deliberate act of mending, piecing him back together. Each one a stark reminder of the unforgiving nature of his profession. He lay there, his face throbbing, the cold steel of the bull’s horn still vivid in his mind, feeling utterly, profoundly, vulnerable.

The next few weeks were a blur of pain medication and the gnawing frustration of enforced idleness. The mirror showed him a stranger, a Frankenstein’s monster of sutures and swelling. But bills didn’t pay themselves, and the calls kept coming. The world of sick cows didn’t pause for a man’s facial injury.

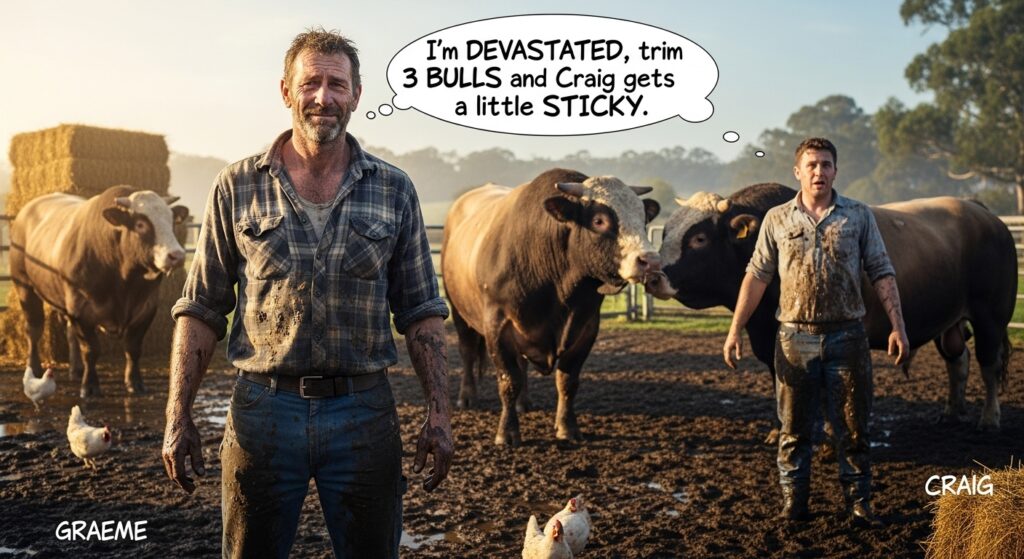

His first week back, the stitches still tight, pulling at his skin, was a brutal reintroduction to reality. He pulled up to the Davidson farm, a cloud of unease hanging over him. He was supposed to trim three bulls. Three magnificent, unpredictable beasts, known for their temperament.

“I’m devastated,” he muttered to himself, not just about the facial injury, the phantom pains, or the gnawing fear that now accompanied every flick of a tail. He was devastated about something else, something deeper, a quiet ache in his chest that had nothing to do with bulls or hooves. It was personal. Too personal to voice.

He forced a smile for Mr. Davidson, the kind of tight-lipped smile that didn’t quite reach his eyes. “Morning, Robert. Ready for these monsters?”

The first two bulls were a challenge, but manageable. He moved slower, more cautiously, his head swiveling constantly, every muscle tensed. He felt the weight of the stitches, the phantom tug as he ducked, adjusted, worked. The third bull, a huge Charolais named Craig, was a different story.

Craig was massive, his hide the colour of creamed coffee, his eyes the colour of obsidian. He bellowed as he entered the chute, a deep, resonant sound that vibrated through Graeme’s bones. He fought the head gate, twisting his neck, snorting plumes of white vapor into the cool morning air.

Graeme worked diligently, his concentration absolute, trying to drown out the internal noise of his own sadness. He cleaned out a deep crack in Craig’s dew claw, then turned his attention to the sole. Just as he was finishing, Craig decided he’d had enough. With a sudden lurch, he twisted, lifting his tail, and let loose.

“Bloody hell, Craig!” Graeme roared, leaping back, but it was too late. A warm, brown cascade erupted, splattering his protective apron, his boots, even a streak across his still-healing cheek.

Mr. Davidson chuckled, a deep, rumbling sound. “Looks like Craig got a little sticky there, Graeme!”

Graeme wiped the mess from his face with the back of a gloved hand, trying to suppress the bile rising in his throat. He looked at his reflection in the polished steel of his hoof knife. A smear of bull faeces, a fresh scar, and eyes that held an ocean of unshed tears. Heartbreak and humour, side-by-side, a constant companion in his working life. He finished the trim, his resolve hardening. The devastation was still there, a dull ache beneath his ribs, but the world, and its demands, continued to turn.

A few months later, the scar on his face had faded to a silvery line, a permanent badge of honour. He’d learned to live with the phantom twinges, the slight tightness when he smiled too wide. But the memory of the bull, the raw power, the sheer unpredictability, remained.

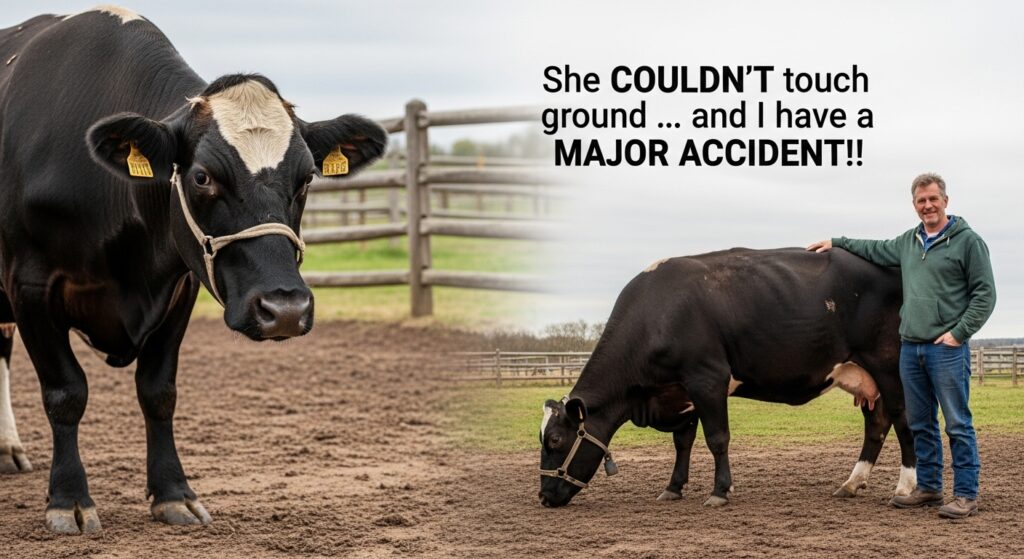

He found himself at the Miller farm, a smaller operation, but with a reputation for meticulous animal care. Mrs. Miller met him at the gate, her face etched with worry. “Graeme, thank goodness you’re here. It’s Daisy. She’s in such pain. She can’t touch the ground with her right front.”

Daisy, a gentle Jersey cow, stood hunched, her right front hoof held aloft, quivering. Her eyes, usually soft and curious, were now wide with distress. Graeme’s heart ached for her. He knew that feeling, the incapacitating pain, the inability to bear weight. He’d been there himself, not just with the bull, but with other incidents, smaller, less dramatic, but equally jarring. A kicked knee, a crushed finger, a concussion from a falling gate. The “major accident” wasn’t a singular event; it was a way of life, a cumulative toll his body quietly kept.

He guided Daisy gently into the chute, his movements slow, reassuring. As he raised her hoof, the severity of the problem became clear. A deep, festering wound, a clear sign of foot rot, had eaten away at a large portion of her sole. It was infected, angry. The stench was immediate, sickening.

“Oh, Daisy, you poor girl,” he murmured, his voice thick with empathy. He took his time, carefully excising the dead tissue, flushing the wound, applying antiseptic paste. Each movement was deliberate, a surgeon’s touch. He imagined her pain, the throb, the inability to move. He remembered his own pain, the stitches, the crushing weight of the bull’s head. The line between their suffering felt incredibly thin.

Just as he was finishing, applying a protective block to the healthy hoof to give the injured one time to heal, a loud crack echoed from behind him. He spun around, adrenaline surging. A rusted hinge on the ancient metal chute had given way, sending a heavy support bar swinging wildly. It caught him square on the shoulder, a sickening thud that stole his breath.

He crumpled, the world spinning. The pain was immediate, sharp, radiating down his arm. He heard Mrs. Miller’s cry, saw Daisy flinch in the chute. It wasn’t as dramatic as the facial injury, no blood gushing, no dramatic fall. But the sudden, jarring impact, the sickening ache, was all too familiar. Another accident. Another reminder. He lay there, his good hand clutching his throbbing shoulder, staring up at the cloudy sky, listening to the rhythmic chewing of Daisy, who now, perhaps, felt a little less pain than he did. The resilience of these animals, their quiet endurance, was both a comfort and a challenge.

The recovery from the shoulder injury was slow, a dull ache that seemed to seep into his very bones. But the world kept turning, and the cows kept getting sore feet. His work wasn’t just a job; it was a calling, a rhythm that grounded him even when his own life felt adrift.

One sunny afternoon, a few weeks after his shoulder had mended enough for him to work without grimacing, he was rechecking a few cows at a small dairy. They were all familiar faces – Big Bertha, with her perpetually muddy hooves; gentle Clara, prone to sole ulcers; and little Dot, a first-calver who’d struggled with laminitis.

As he worked, paring a small lesion on Clara’s hind foot, his mind drifted. He thought about his daughter. Sarah. She was sixteen now, a whirlwind of vibrant energy and quiet intensity. She’d been struggling lately, with school, with friends, with the bewildering maze of teenage life. He missed her, truly missed her. Their conversations had become shorter, punctuated by silences, by the click of a phone screen.

He remembered a time, not so long ago, when she would sit in the passenger seat of his muddy truck, her small hands clutching a worn copy of a children’s book, reading aloud as he drove from farm to farm. She’d always been curious, asking about the cows, about the tools, about the specific smell of disinfectant and manure. He remembered her face, lit up with wonder as he explained how a healthy hoof supported the animal, how a small problem could lead to great pain.

“Dad, does it hurt them when you cut their hooves?” she’d asked once, her brow furrowed with concern.

“Only if they’re sick, sweetie,” he’d replied, ruffling her hair. “Then it hurts for a little bit, but then it makes them better.”

He paused his work, the grinder falling silent. He looked at Clara, now standing patiently, her breath warm on his hand. He’d helped her. He’d fixed her. And he wondered, with a fresh ache in his chest, if he was doing enough for Sarah. Had he been too busy with the suffering of animals to truly see the suffering of his own daughter?

He felt a sudden, overwhelming urge to talk to her. Not about school, not about chores, but about her. About the quiet ache he sensed, the unspoken worries. He knew he often presented himself as stoic, the unflappable man of the land, capable of handling any crisis. But deep down, he was as vulnerable as the next person, perhaps more so. The devastation from months ago, that unnamed ache, often returned when he thought of Sarah, of their growing distance.

He finished with Clara, then moved to Dot, whose laminitic hooves needed careful re-evaluation. He cleaned the sole, checked the sole depth, making sure the blocks he’d applied were still secure. His hands moved with expertise, but his mind was elsewhere, drafting a conversation, rehearsing words he needed to say.

“We need to talk, honey,” he’d start. No, too formal. “How are you, really?” Better. He pictured her face, her expressive eyes. He would tell her about his own struggles, about the fears that came with his job, about the pain he’d endured. He would open up, truly open up, as he hadn’t done in years. He realized, looking at Dot, who was now standing with slightly more comfort, that the same care, the same patient attention he gave to these animals, was what his daughter needed from him. He couldn’t fix her problems with a hoof knife, but he could offer the space, the listening ear, the unwavering presence.

He packed up his tools, the sun beginning its slow descent, painting the sky in hues of orange and purple. The day’s work was done. The cows were, for now, a little better. He looked at his scarred hand, then up at the vast, open sky. He was just a hoof trimmer, a man who dealt with the rough realities of farm life, with animal pain and physical danger. But he was also a father, a man navigating the complexities of the human heart, his own and his daughter’s.

Graeme drove home, the scent of antiseptic and cow dung clinging to his clothes, a constant reminder of his day. The silence in the truck was different tonight, no longer a heavy blanket, but a canvas on which new thoughts were painted. He thought of the stone he’d removed from the bull’s hoof, the tiny irritant that could cause so much suffering. He thought of the bull’s blind rage, the stitches, the lingering phantom pain in his face. He thought of Craig getting “sticky,” a moment of pure, unadulterated farm chaos that had momentarily cut through his own deep sadness. He thought of Daisy, unable to touch the ground, and his own shoulder, screaming in protest. And he thought of Sarah, his daughter, her silent struggles echoing the unspoken pain of the animals he tended.

His work, with all its dangers and devastation, its moments of grim humour and profound empathy, had taught him resilience. It had taught him to observe, to listen, to feel. It had shown him that healing wasn’t always a straight path, and that sometimes, the most important stitches were the ones we put into our own lives, mending not just skin, but spirit.

He pulled into his driveway, the familiar silhouette of his home a comforting sight. He took a deep breath, steeling himself not for another confrontation with a bull, but for a conversation with his daughter. He carried the day’s experiences with him – the dirt, the sweat, the ache in his muscles, the quiet understanding that had blossomed in his heart.

He knew that life, like a cow’s hoof, would always present new challenges, new wounds. But he also knew that with care, with patience, and with an open heart, even the deepest cuts could heal, and even the most vulnerable could learn to stand firm, to walk freely, and to face another day. He stepped out of the truck, ready to trim the edges of his own life, and perhaps, finally, mend the unseen wounds within.