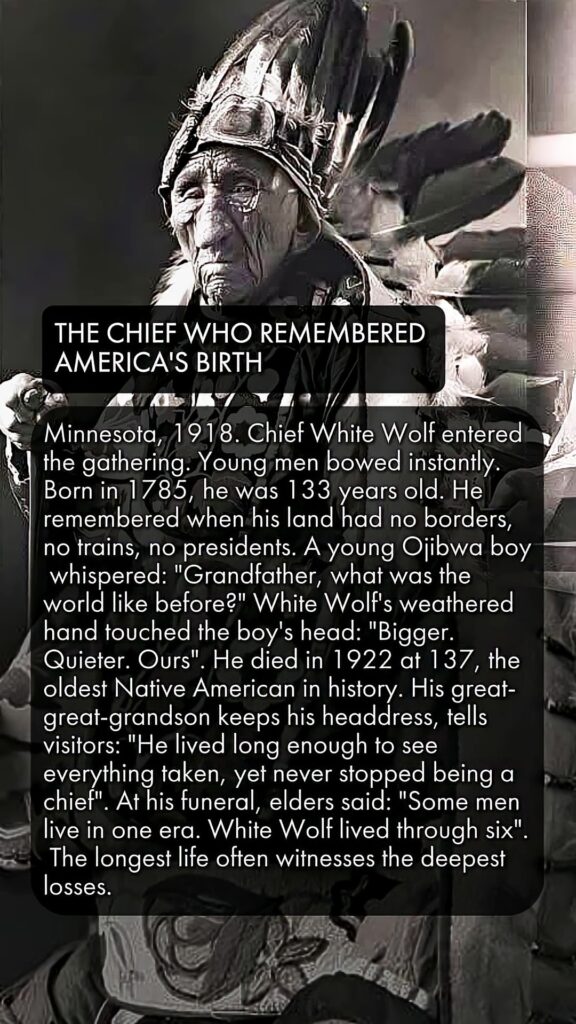

THE CHIEF WHO REMEMBERED AMERICA’S BIRTH Minnesota, 1918. Chief White Wolf entered the gathering. Young men looked intently. Born in 1785, he was 133 years old. He remembered when his land had no borders, no trains, no presidents. A young Ojibwa boy whispered: “Grandfather, what was the world like before?” White Wolf’s weathered hand touched the boy’s head: “Bigger. Quieter. Ours.” He died in 1922 at 137, the oldest Native American in history. His great-great-grandson keeps his headdresses, tells visitors: “He lived long enough to see everything taken, yet never stopped being a chief.” At his funeral, elders said: “Some men live long lives. White Wolf lived through such time.” The longest life often witnesses the deepest losses.

Chief White Wolf, also known as John Smith, was a Chippewa (Ojibwa) elder whose life spanned an era of unimaginable change. Born sometime between 1785 and 1825—though he claimed the earlier date—he lived in the forests near Cass Lake, Minnesota, and was said to have reached the age of 137 before his death in 1922.

His face, deeply wrinkled and weathered, earned him the nickname “Ga-Be-Nah-Gewn-Wonce,” meaning “Wrinkled Meat.” But behind those lines was a memory that stretched back to a time before trains, before presidents, before borders. He remembered a world where the land was open, quiet, and wholly Native. When asked by a young Ojibwa boy what the world was like before, he replied simply: “Bigger. Quieter. Ours.”

Chief White Wolf’s life was marked not just by longevity, but by endurance. He lived through the forced displacement of his people, the signing of treaties that stripped away land, and the rise of a country that often ignored the voices of its first inhabitants. Yet he remained a chief—not just in title, but in spirit. He carried the wisdom of generations, and even in his final years, he was revered by younger Native men who saw in him a living connection to a lost world.

In 1920, he was featured in a traveling motion picture exhibition showcasing aged Native Americans, a rare moment of visibility for a man whose life had largely been lived in quiet resistance. At his funeral, tribal elders said, “Some men live long lives. White Wolf lived through such time.” His great-great-grandson still keeps his headdresses and tells visitors, “He lived long enough to see everything taken, yet never stopped being a chief.”

While historians debate the accuracy of his age—some records suggest he was born closer to 1825—the symbolic weight of his story remains. Chief White Wolf represents the endurance of Native identity in the face of erasure. His life reminds us that the longest lives often bear witness to the deepest losses—but also carry the deepest truths.