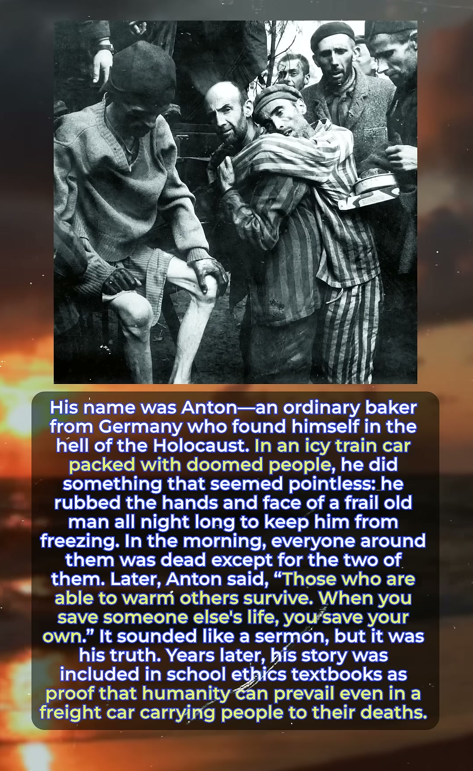

His name was Anton—an ordinary baker from Germany who found himself in the hell of the Holocaust. In an icy train car packed with doomed people, he did something that seemed pointless: he rubbed the hands and face of a frail old man all night long to keep him from freezing. In the morning, everyone around them was dead except for the two of them. Later, Anton said, “Those who are able to warm others survive. When you save someone else’s life, you save your own.” It sounded like a sermon, but it was his truth. Years later, his story was included in school ethics textbooks as proof that humanity can prevail even in a freight car carrying people to their deaths.

His name was Anton, a humble baker from Germany. He wasn’t a soldier, a scholar, or a leader. He was just a man who knew how to knead dough and offer warmth. But in 1943, that warmth became his weapon against death.

Anton was deported during the Holocaust, crammed into a frozen cattle car with dozens of others. The train rattled through the night, its metal walls trapping cold and despair. People screamed, wept, then fell silent. The temperature dropped. Breath turned to frost. Hope evaporated.

In that darkness, Anton noticed an elderly man, barely conscious, his skin turning blue. Anton didn’t have blankets. He didn’t have medicine. But he had his hands. So he rubbed the man’s face, his fingers, his chest—for hours. No sleep. No food. Just friction and faith.

By morning, everyone else in the car was dead. Only Anton and the old man survived.

Later, when asked how he endured, Anton said: “Those who are able to warm others survive. When you save someone else’s life, you save your own.”

It wasn’t metaphor. It was physics. It was psychology. It was humanity.

Anton’s story spread. It was eventually included in school ethics textbooks, taught as a lesson in compassion under cruelty. He became a symbol—not of resistance, but of resilience. Of how human connection can defy even genocide.

He never sought recognition. He returned to baking. But his legacy lived on—in classrooms, in sermons, in quiet conversations about what it means to be truly human.

The Holocaust claimed millions. But Anton’s story reminds us that even in the darkest boxcars, light can be passed hand to hand.