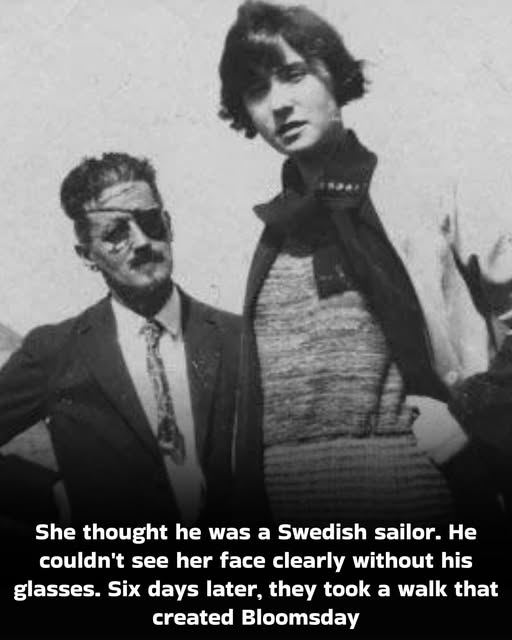

On June 10, 1904, a twenty-two-year-old with bad eyesight was walking down Nassau Street in Dublin. He noticed a young woman with auburn hair and an upright carriage he would later describe as “queenly.”

He was wearing a yachting cap. She mistook him for a Swedish sailor.

Her name was Nora Barnacle. She was twenty years old, recently arrived from Galway, working as a chambermaid at Finn’s Hotel. She had fled a difficult home—her father absent, raised by strict uncles—and was finding her way in the city alone.

When the young man spoke to her, she was skeptical. But something in his manner—polite, persistent, earnest despite his obvious nervousness—convinced her to agree to meet him again.

His name was James Joyce. He had just graduated from university. He was writing poetry, dreaming of Paris, struggling to find his voice as an author. He had no idea he would become one of the most revolutionary writers of the twentieth century. At that moment, he was just a young man with a yachting cap, trying to convince a beautiful girl from Galway to take a chance on him.

They arranged to meet on June 14, outside the house of Oscar Wilde’s father on Merrion Square.

Joyce arrived at the appointed time. Nora didn’t show.

That night, heartbroken, he went home and wrote her a note:

“I may be blind. I looked for a long time at a head of reddish-brown hair and decided it was not yours. I went home quite dejected. I would like to make an appointment but it might not suit you. I hope you will be kind enough to make one with me—if you have not forgotten me!”

She had not forgotten him.

They rescheduled for June 16.

That evening, they walked together toward Ringsend, a coastal area on the edge of Dublin. Away from the city’s prying eyes, something shifted between them. Nora was direct, earthy, unimpressed by Joyce’s intellectual pretensions—but drawn to his vulnerability. Joyce, who had spent his youth in Jesuit schools, surrounded by abstractions and theories, found in her a raw, vital honesty that nothing in his education had prepared him for.

By the end of that walk, Joyce was transformed. He later told her: “You made me a man.”

He meant it in every sense. That evening awakened something in him—not just romantically, but creatively. He realized that this “uneducated” chambermaid from Galway possessed a truth his books lacked. She became his connection to the real Ireland, to the rhythms of ordinary life, to the body and the earth.

Eighteen years later, when Joyce finished his masterpiece Ulysses, he set the entire novel on a single day: June 16, 1904. Every event in that massive book—every wandering thought of Leopold Bloom, every scene in Dublin’s streets and pubs and brothels—takes place on the day Joyce first walked with Nora.

It was his most eloquent tribute to her. His biographer Richard Ellmann wrote: “To set Ulysses on this date was Joyce’s most eloquent if indirect tribute to Nora, a recognition of the determining effect upon his life of his attachment to her.”

That date is now known worldwide as Bloomsday. Each June 16, fans dress in Edwardian costume, read passages aloud, retrace Bloom’s footsteps through Dublin, and celebrate the novel. Few of them realize they’re also celebrating a first date.

The connection sparked that night lasted through decades of hardship. Four months after meeting, Joyce convinced Nora to leave Ireland with him—unmarried, scandalously, to the Continent. They settled in Trieste, then part of Austria-Hungary. They had two children: Giorgio in 1905, Lucia in 1907.

For years, they lived in grinding poverty. Joyce taught English to earn money while writing at night. They were evicted repeatedly, moving from flat to flat, country to country. Nora took in laundry to help support the family. She learned Italian, managed the household, and endured her husband’s drinking, his eccentricities, and his obsessive devotion to his work.

She also became his muse. The character of Molly Bloom in Ulysses—her voice, her earthiness, her famous final monologue—was drawn directly from Nora. Gretta Conroy in “The Dead,” perhaps Joyce’s most moving short story, was inspired by Nora’s memories of a young man who died for love of her in Galway.

Joyce’s letters to Nora are among the most passionate in literary history. Some are shockingly erotic; others are pure devotion. In one, he wrote: “Nora, I love you. I cannot live without you. I would like to give you everything that is mine… I would like to go through life side by side with you, telling you more and more until we grew to be one being together until the hour should come for us to die.”

Through it all, Joyce’s eyes failed him. He suffered from iritis, glaucoma, and cataracts. Over the course of his life, he underwent more than a dozen eye surgeries—all without general anesthesia. By 1930, he was practically blind in his left eye, his right eye barely functional. He wrote with red crayon on large white sheets, used magnifying glasses, wore an eye patch, and eventually dictated much of his final work, Finnegans Wake.

Nora stayed by his side through every surgery, every recovery, every moment of despair. She bathed his eyes with ice water during attacks. She read to him when he couldn’t see. She managed his affairs when he was incapacitated. She was, as one scholar put it, “his anchor.”

After living together for twenty-seven years and having two children, Joyce and Nora finally married in 1931—not for romance, but to secure their children’s inheritance under British law. In photographs from their London wedding, Joyce looks grim; Nora hides her face with her hat. Neither enjoyed the attention. But the legal formality changed nothing between them. They had been partners, in every meaningful sense, for nearly three decades.

When World War II forced them to flee Paris in 1940, they returned to Zurich—the city where they had found refuge during World War I, where Joyce had written much of Ulysses. On January 13, 1941, Joyce died there after surgery for a perforated ulcer. He was fifty-eight.

Nora asked the Irish government to repatriate his body. They refused. The country that Joyce had immortalized in his fiction, the city he had captured so completely that scholars say Dublin could be reconstructed from his books—they wanted no part of him in death.

Nora stayed in Zurich. She died there on April 10, 1951.

In 1966, her remains were exhumed and reburied beside her husband in Fluntern Cemetery. A bronze statue of Joyce—seated, book in hand, cigarette between his fingers—watches over them both.

Today, the grave is a pilgrimage site. Readers come from around the world to pay respects to the man who changed literature—and to the woman from Galway who changed him.

They rest together on a Swiss hillside, far from the Dublin streets where they first met. But every June 16, when readers celebrate Bloomsday, they’re also celebrating a walk to Ringsend, a first date, a young man and woman discovering that they had found something worth holding onto—absolutely, forever.