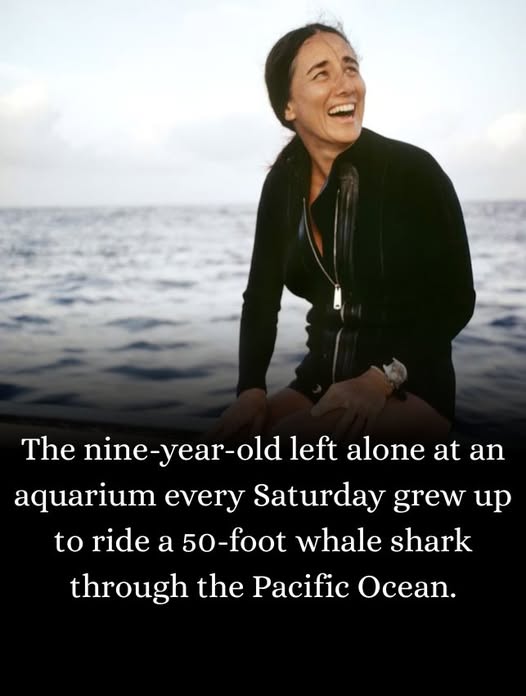

The nine-year-old left alone at an aquarium every Saturday grew up to ride a 50-foot whale shark through the Pacific Ocean. New York City, 1924. Eugenie Clark was two years old when her father died. Her mother, Yumico, a Japanese immigrant, had to work. No family nearby. No childcare options. No safety net. So she got creative. Every Saturday morning, Yumico dropped young Eugenie at the New York Aquarium in Battery Park before heading to her newspaper stand in Manhattan. She’d return hours later to collect her daughter. Most children would have been bored, frightened, lonely. Eugenie was mesmerized. She wandered the old aquarium housed in Castle Clinton, pressing her nose against glass tanks, watching fish glide through the water. Sharks especially fascinated her—the way they moved, the way they looked, the way everyone else seemed terrified of them but she found them beautiful.

She spent every Saturday there. Watching. Learning. Dreaming. She decided: someday, she would swim with sharks. Her mother bought her a small tank of guppies. Eugenie filled it with fish, toads, snakes, even a small alligator. She wrote all her school reports on marine biology. She told anyone who would listen that she wanted to be an ichthyologist—a fish biologist. The 1940s weren’t exactly welcoming to women in science. Especially not Japanese-American women during and after World War II. Especially not women who wanted to study sharks. Eugenie didn’t care what the world was ready for. She earned her Bachelor’s degree from Hunter College in 1942. Her Master’s in 1946 from NYU. She worked as a chemist at a plastics company to pay tuition. In 1950, she completed her Ph.D. in zoology.

Then she learned to scuba dive. This was revolutionary. In the 1940s and 50s, most marine biologists studied dead specimens in laboratories. They dissected preserved fish. They examined dried sharks. They made theories based on corpses. Eugenie wanted to study living creatures. In their natural environment. Behaving naturally. She became a pioneer in using scuba gear for underwater scientific research—one of the first ichthyologists to observe fish and sharks alive, in the wild, on their own terms. In 1950, as a Fulbright Scholar, she conducted research in the virtually unexplored waters of the Red Sea. She discovered several new fish species. One—the Moses sole—produced a natural shark repellent when threatened. She watched sharks approach the Moses sole aggressively, then suddenly stop and thrash their heads side to side, repelled by the chemical the fish secreted. It was the first naturally occurring shark repellent ever discovered. Her 1953 memoir about her Red Sea adventures, Lady with a Spear, became an international bestseller. Suddenly, people who had never thought about marine biology were reading about this fearless woman diving in remote waters, studying creatures most people feared.

Among her readers: Anne and William Vanderbilt, wealthy philanthropists who owned property in southwest Florida. They contacted Eugenie with a proposal: What if we built you a laboratory? What if you could conduct shark research full-time? In 1955, the Cape Haze Marine Laboratory opened in Placida, Florida. It was essentially a one-room building. Eugenie’s only assistant was a local fisherman named Beryl Chadwick who knew how to catch sharks. From that tiny lab, Eugenie would transform how the world understood sharks. In 1958, she began behavioral experiments with lemon sharks. The prevailing scientific belief was that sharks were stupid, primitive killing machines—mindless predators operating on pure instinct. Eugenie trained sharks to press targets to receive food rewards. She proved sharks could learn. They could remember. They had intelligence. They weren’t mindless at all. It was groundbreaking research that contradicted everything scientists thought they knew. Then came the “sleeping sharks.” In 1973, Eugenie visited underwater caves in Mexico where fishermen reported seeing sharks lying motionless. This shouldn’t have been possible. Everyone knew sharks had to keep moving constantly to breathe—water had to flow over their gills or they’d suffocate.

Eugenie dove into those caves and found sharks suspended in the water, seemingly asleep, perfectly still. She hypothesized that freshwater seeps in the caves created conditions where sharks could rest without swimming. The presence of parasite-eating remoras in the caves suggested sharks visited specifically to shed parasites. She had disproven another “fact” everyone accepted about sharks. Over her career, Eugenie led over 200 field research expeditions worldwide. She conducted 72 deep submersible dives—some reaching depths of 12,000 feet. She wrote over 175 scientific articles. She discovered numerous fish species. She had multiple species named in her honor, including Squalus clarkae—Genie’s dogfish. She taught at the University of Maryland for 24 years. She wrote extensively for National Geographic. She appeared on television programs. She gave lectures from elementary schools to royal audiences—Japanese Emperor Akihito, himself an ichthyologist, invited her to teach him to skin dive at 5 a.m. And she did. In 1975, the movie Jaws terrified millions and demonized sharks as mindless killers. Eugenie fought back with science and storytelling. She wrote articles titled “Sharks: Magnificent and Misunderstood.” She gave talks explaining shark behavior, shark intelligence, shark importance to marine ecosystems. “These ‘gangsters of the deep’ have gotten a bad rap,” she said. “No creature on earth has a worse, and perhaps less deserved, reputation than the shark.”

She worked tirelessly to change public perception. Not because she was naive about shark danger—she understood they were apex predators—but because she knew that fear leads to killing, and killing leads to ecosystem collapse. Then came the whale shark moment. In the Sea of Cortez, photographer David Doubilet watched in disbelief as Eugenie—already in her later years—swam up to a 50-foot whale shark, the largest fish in the sea, grabbed its dorsal fin, and held on. She rode that whale shark through the Pacific. Doubilet thought he’d never see her again. She later called it one of the most exciting journeys of her career. That was Eugenie. Even in her seventies and eighties, she couldn’t resist the adventure. Couldn’t resist getting closer to the creatures she loved. Her Cape Haze Marine Laboratory eventually became Mote Marine Laboratory—now a world-renowned research facility in Sarasota, Florida, conducting cutting-edge research on sharks, coral reefs, wild fisheries, and marine conservation. In June 2014, at age 92, Eugenie made her final dive. Eight months later, on February 25, 2015, she died from lung cancer.

She had spent 72 years—from that first Saturday at the aquarium in 1924 to her last dive in 2014—devoted to fish, sharks, and the ocean. Here’s what Eugenie Clark proved: The little girl everyone left behind became the woman everyone followed. The “stupid killing machines” she studied turned out to be intelligent, complex, essential. The career everyone said was impossible for a woman became a 60-year legacy of discovery. She didn’t just study sharks. She changed how the entire world sees them. Today, girls can press their noses against aquarium glass and look at fish species named after Eugenie Clark. They can read her books. They can follow her path into marine biology. They can become the next Shark Lady. Because she showed them it was possible.