“For 4 years, she sat at a desk while Nazis looted 20,000 artworks around her—and they never knew she understood every word they said.” Paris, October 1940. The Nazis had just commandeered the Jeu de Paume museum, transforming it into their central headquarters for sorting stolen art. Masterpieces looted from Jewish families would be catalogued here before shipment to Germany. And the quiet woman working at the museum? To them, she was nobody. Just a clerk. Harmless. Forgettable. That assumption would become one of their costliest mistakes.

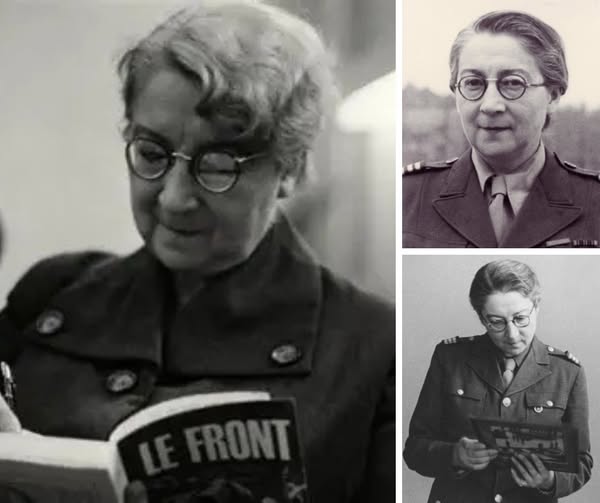

Rose Valland was 42, an unpaid volunteer curator with degrees from the École du Louvre and the Sorbonne. When the Nazis arrived, France’s museum director gave her a deadly assignment: stay at your post, observe everything, and document their crimes. Most people would have fled. Rose chose to fight. Every day, she watched crates arrive carrying treasures stolen from Jewish families. Paintings by Vermeer, Monet, Cézanne, Renoir. Entire collections that represented lifetimes of beauty and memory, seized under the Nazi lie of “protection.” Hermann Göring—Hitler’s second-in-command—visited the museum twenty-one times, personally selecting masterpieces for his castle. Rose was there each time, appearing dutiful and insignificant. But the Nazis made one fatal miscalculation. They never knew Rose spoke fluent German.

For four years, she maintained this deception without a single slip. She listened as officers discussed shipments. She memorized train car numbers. She tracked which masterpieces were going where. Every night, she wrote it all down in secret notebooks. The risk was absolute. If discovered, she would be executed immediately as a spy. Yet Rose continued, passing information to the French Resistance so they wouldn’t accidentally destroy trains carrying France’s cultural treasures during sabotage operations. In July 1943, she witnessed something that haunted her forever. The Nazis brought 500 paintings to the museum’s terrace—works by Picasso, Miró, and Klee they deemed “degenerate.” They piled them high and set them on fire. Rose watched from inside as masterpieces flickered in flames and disappeared into smoke. She was powerless to stop it. All she could do was document what was lost and keep working. As Allied forces approached Paris in August 1944, the Nazis grew frantic. On August 1, Rose discovered that 148 crates containing works by Cézanne, Monet, and Renoir had been loaded onto train cars headed for Austria.

She had the rail car numbers. She passed them to the Resistance. French troops intercepted the train before it crossed the border, saving irreplaceable masterpieces from almost certain destruction. When Paris was liberated on August 25, 1944, Rose was initially arrested as a suspected Nazi collaborator simply because she had worked at the museum throughout the occupation. Only after her conduct was vouched for was she released. What she revealed to the Allies stunned everyone. Rose possessed detailed records of more than 20,000 artworks that had passed through the Jeu de Paume. She had shipping manifests. Destinations. Storage locations. Her documentation was so precise it became a treasure map for recovering looted art across Germany. On May 4, 1945, Rose received a commission as a lieutenant in the French First Army. She refused to stay in Paris. She traveled to Germany with the Monuments Men, personally overseeing recovery operations for eight years. Her records led Allied forces to Neuschwanstein Castle, where over 20,000 works were hidden. But she didn’t stop there. She tracked down German officers she’d documented during the occupation and interviewed them, discovering additional hiding places no one else knew existed—mines, castles, bunkers filled with stolen treasures. In February 1946, Rose Valland stood at the Nuremberg trials and confronted Hermann Göring. The quiet clerk he had never considered a threat presented evidence of his crimes, named specific stolen pieces, and detailed every one of his twenty-one visits to the museum.One of the most powerful men in Nazi Germany was forced to answer to the woman he’d completely dismissed.

By the time her work concluded, Rose had been instrumental in recovering approximately 60,000 artworks. Of these, 45,000 were returned to their rightful owners—many to Jewish families who had lost everything else. The art represented not just value, but identity, heritage, and memory.

Captain James Rorimer, who became director of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, wrote: “The one person who above all others enabled us to track down Nazi art looters was Mademoiselle Rose Valland, a rugged, painstaking and deliberate scholar.”

Rose became one of the most decorated women in French history, receiving the Légion d’honneur and numerous other honors. Yet she never sought fame. She returned to work as a museum curator and continued assisting in art restitution efforts until her death in 1980.

Her archives remain a valuable resource for recovering stolen World War II art today.

Rose Valland never fired a weapon. She didn’t sabotage trains or hide refugees. Her act of defiance was quieter but no less courageous: she catalogued truth. She preserved memory. She documented theft so meticulously that justice became possible.

For four years, she sat at a desk, moving a pen across a page, while the Nazis around her discussed their crimes in a language they thought she couldn’t understand.

Her greatest weapon was being underestimated.

And in that invisibility, she saved fragments of 60,000 lives the Nazis tried to erase—one careful notation at a time.