In 1912, a German scientist looked at a map and saw something that would cost him his life—but change our understanding of Earth forever. Alfred Wegener was studying meteorology when he glanced at a world map and froze. The coastlines of Africa and South America—they matched. Perfectly. Like two pieces torn from the same puzzle. But it wasn’t just those two. Europe and North America. Antarctica and Australia. Madagascar and India. What if, Wegener wondered, they hadn’t always been separated by oceans? What if, millions of years ago, they had been one? He called it Pangaea—the ancient supercontinent. And he proposed something that seemed impossible: continental drift. The idea that continents weren’t fixed, but slowly moving across the Earth’s surface. It was brilliant.

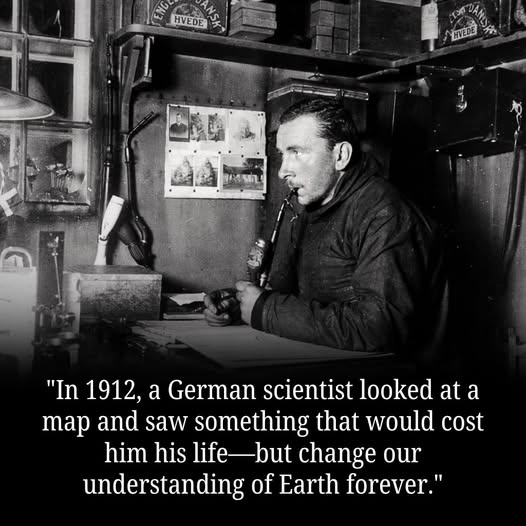

Revolutionary. Logical. And the scientific community destroyed him for it. “Continents don’t move,” geologists scoffed. “That’s absurd.” They called his theory “utter rot” and “footloose.” One prominent scientist said it was “as if we were to assume that the Earth’s crust is made of pumpkin.” The problem? Wegener couldn’t explain the mechanism. He knew the continents must be drifting—the evidence was overwhelming—but the science to explain how wouldn’t exist for another 50 years. Still, he didn’t give up. He spent years gathering evidence: matching fossils on opposite sides of oceans, identical rock formations on distant continents, ancient climate patterns that only made sense if landmasses had shifted. In November 1930, Wegener led his fourth expedition to Greenland, determined to gather more proof. He was 50 years old, pushing through brutal Arctic conditions to resupply a remote research station. On November 1st, Wegener and his companion set out for the return journey in −60°F weather. They never made it back. Six months later, in May 1931, searchers found Wegener’s body buried beneath the snow. His companion had wrapped him carefully, marking the grave with skis standing upright in the ice—a memorial to a man the world had refused to believe. His theory remained buried with him. Dismissed. Forgotten. For three decades. Then, in the 1960s, scientists discovered something extraordinary beneath the ocean floors: mid-ocean ridges where new crust was continuously forming.

Magnetic patterns in rocks that recorded Earth’s history. Evidence of massive tectonic plates shifting beneath our feet. Everything clicked. Wegener had been right all along. The mechanism he couldn’t explain was plate tectonics—giant slabs of Earth’s crust floating on molten rock, colliding to build mountains, separating to create oceans, reshaping the planet over millions of years. Every prediction Wegener made was validated. Every mockery he endured was proven wrong. Today, his name appears in every geology textbook. Students learn about Pangaea in elementary school. Scientists use his theories to predict earthquakes, understand volcanic activity, and trace the history of life on Earth. But Alfred Wegener never saw his vindication. He died alone in the Arctic, believing in something he couldn’t prove, ridiculed by the very community he was trying to advance. And yet he kept going. Not for fame. Not for approval. But because when you see the truth, you can’t unsee it. The continents were moving. The Earth was alive beneath our feet. He saw it when everyone else was blind. Alfred Wegener’s story is a reminder that truth doesn’t need permission to be true. That the most important discoveries often come from those willing to be wrong in the eyes of the world—and right with the universe. Sometimes the bravest thing you can do is look at what everyone else sees and ask a question no one else dares to ask. Sometimes the most powerful legacy isn’t the one you live to see. It’s the one that changes everything after you’re gone. Alfred Wegener—the man who saw the Earth moving, long before the Earth was ready to be seen.