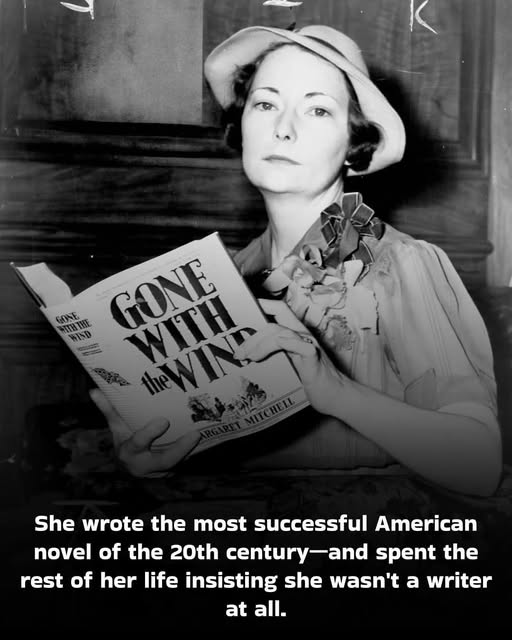

She wrote the most successful American novel of the 20th century—and spent the rest of her life insisting she wasn’t a writer at all.

Her name was Margaret Mitchell. And the complicated, troubling legacy of Gone With the Wind began with a woman who never wanted to be famous and didn’t believe she had any business writing a book in the first place.

In 1926, Margaret Mitchell was a 26-year-old former journalist in Atlanta, recovering from a severe ankle injury that had ended her newspaper career. Bored, restless, and stuck at home, her husband brought her a stack of library books to pass the time.

She read them all in days.

“There’s nothing left to read,” she complained.

Her husband looked at her and said: “Well, then write one yourself.”

So she did. Out of spite, out of boredom, out of having nothing else to do.

For the next ten years, she wrote in secret. She told almost no one. She wrote on a rickety typewriter, on whatever paper she could find—the backs of old manuscripts, cheap yellow paper, scraps. The chapters piled up in disorganized stacks around her apartment, some in envelopes, some just loose.

She had no plan. She didn’t write chronologically—she wrote whatever scenes interested her that day. The first chapter she wrote was actually the last chapter of the book. She had no outline, no publishing ambitions, no belief that anyone would ever read what she was creating.

She was just… writing. Filling the void of her injury-bound life with a sprawling story about a spoiled Southern belle named Pansy O’Hara (later renamed Scarlett) who refused to be broken by war, poverty, or societal expectations.

By 1935, she had a manuscript nearly a thousand pages long. It was messy, disorganized, missing chapters. She’d never shown it to anyone except her husband.

Then a book scout from Macmillan Publishing visited Atlanta, looking for Southern authors.

A mutual friend insisted Margaret had written something. Margaret, mortified, denied it. She literally lied and said there was no manuscript.

But the scout persisted. And something in Margaret snapped—the same stubbornness that would define Scarlett O’Hara.

She went home, grabbed the chaotic pile of manuscript pages, stuffed them into a suitcase, and brought them to the scout’s hotel.

“Here,” she said, shoving the suitcase at him. “Take it before I change my mind.”

She immediately regretted it. She tried to get the manuscript back. The scout refused. He’d already started reading—and he was stunned.

Gone With the Wind was published on June 30, 1936.

Within six months, it had sold one million copies—the fastest-selling novel in publishing history at that time. It won the Pulitzer Prize in 1937. The film rights sold for a record-breaking $50,000.

Margaret Mitchell, the woman who insisted she wasn’t a writer, had created a cultural phenomenon.

And she hated it.

The fame was suffocating. Thousands of letters poured in—from fans, from critics, from people demanding she write more books, from Southerners praising her “accurate” portrayal of the Old South, from people asking for money, for autographs, for pieces of her time.

She answered every single letter personally. All of them. For years.

It consumed her life. She stopped writing entirely. When people asked about a second novel, she’d say she had nothing more to write. The success of Gone With the Wind had drained her completely.

But here’s where the story gets complicated—because we have to talk about what that book actually was.

Gone With the Wind is a romanticized fantasy of the Confederate South. It portrays enslaved people as loyal servants content with their bondage. It frames Reconstruction—the period when Black Americans briefly gained political power—as a corrupt catastrophe. It presents the Ku Klux Klan sympathetically.

The book is steeped in Lost Cause mythology—the false narrative that the Confederacy was noble, that slavery wasn’t that bad, that the antebellum South was a gracious civilization destroyed by Northern aggression.

Margaret Mitchell wrote this mythology as truth. She drew from family stories told by people who’d been Confederate sympathizers, who’d owned enslaved people, who’d lost wealth and status after the war.

She wasn’t trying to write a racist book. She genuinely believed she was writing Southern history accurately.

That’s what makes it so insidious.

Gone With the Wind shaped how millions of Americans—and people worldwide—understood the Civil War. The film, with its gorgeous cinematography and sweeping romance, embedded these false narratives even deeper.

For decades, people believed Scarlett O’Hara’s story was historically accurate. That the “happy slaves” depicted were realistic. That Reconstruction was a tragedy for white Southerners rather than a brief, precious moment of Black freedom brutally crushed.

The novel did massive cultural harm. It reinforced racist stereotypes at a time when Jim Crow laws oppressed Black Americans across the South. It made nostalgia for the Confederacy seem romantic rather than horrifying.

Margaret Mitchell didn’t live to see the full reckoning with her book’s legacy. She died in 1949, struck by a car while crossing an Atlanta street. She was 48 years old.

She never wrote another novel. Never wanted to.

The woman who created one of the most successful books in American history spent thirteen years being devoured by its fame, answering letters, attending events, watching her privacy disappear—and then was gone.

What do we do with Margaret Mitchell?

We can’t erase Gone With the Wind from history. It exists. Millions of people still read it. The film is still celebrated for its technical achievements.

But we also can’t pretend it’s harmless nostalgia.

It’s a beautifully written book that promotes deeply harmful lies. It’s a compelling story built on racist mythology. It’s a cultural touchstone that shaped American racism for generations.

Margaret Mitchell wasn’t a monster. She was a talented writer, a product of her time and place, someone who genuinely believed the Confederate narrative she’d been taught.

But being a product of your time doesn’t make the harm disappear.

Her book sold 30 million copies. It won a Pulitzer. It became an Oscar-winning film. And it taught millions of people a false, romanticized version of history that made slavery seem benign and Black freedom seem threatening.

That’s her legacy—both the extraordinary literary achievement and the extraordinary harm.

The woman who never wanted to be a writer created a book that won’t let us forget her.

For better and for worse.