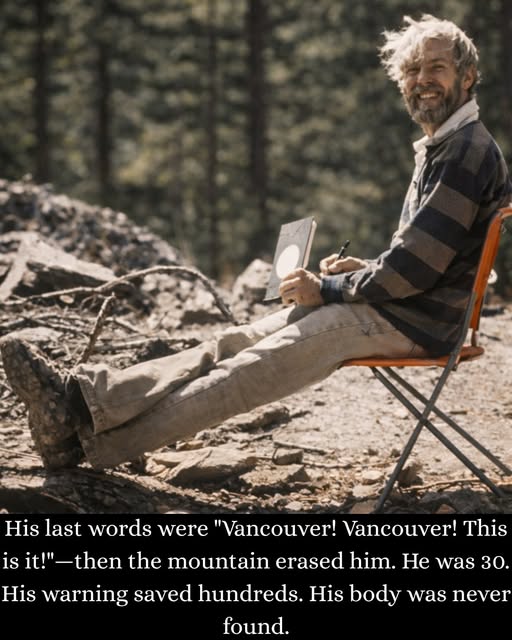

He was 30. His warning saved hundreds. His body was never found. May 18, 1980. Dawn broke over the Cascade Range in Washington State, and David A. Johnston was exactly where he’d been for weeks: watching Mount St. Helens. He’d barely slept. For 57 days, the mountain had been building toward something catastrophic. Earthquakes rattling the ground. Steam vents blasting through snow. A massive bulge swelling on the north face—the mountain literally deforming as magma pushed upward from below, growing outward at over five feet per day.

David was stationed at Coldwater II—an observation post six miles north of the volcano’s summit. Just a ridge with monitoring equipment, a trailer, and a radio. But it had a clear view of the mountain. And David Johnston was determined to understand what it was about to do. He was a volcanologist with the U.S. Geological Survey. Colleagues described him as brilliant, meticulous, careful—the kind of scientist who checked his data twice and never overstated his conclusions. David had studied volcanoes around the world, sampled gases from active vents, climbed into craters, faced danger with calculated caution. But Mount St. Helens was different. This volcano had been sleeping for 123 years. Now it was waking up—and it was angry. The mountain had started rumbling in March. Small earthquakes, then larger ones. Steam explosions. That terrifying bulge on the north face, swelling like a tumor about to burst.

David and his USGS colleagues knew the mountain could erupt catastrophically. The question was when. Local residents didn’t want to leave. Property owners resisted evacuation orders. Some thought scientists were overreacting. One man—Harry R. Truman, an 83-year-old lodge owner—refused to evacuate and became a folk hero for his defiance. David understood the frustration. Evacuations were disruptive, economically painful, based on uncertain predictions. But he also knew the mountain could kill thousands if the eruption caught people unprepared. So he kept measuring. Kept monitoring. Kept warning. On May 17, David drove up to Coldwater II to relieve another geologist for the night shift. Routine monitoring. Watch the instruments. Record data. Radio in observations. That night, the mountain was relatively quiet. As dawn broke on May 18, David was still at his post, watching. At 8:32 AM, everything changed. A magnitude 5.1 earthquake struck directly beneath Mount St. Helens. The shaking triggered the catastrophic failure everyone had feared.

The entire north face—that massive, swelling bulge—suddenly collapsed in the largest landslide in recorded history. Two-thirds of a cubic mile of rock, ice, and debris roared down the mountain at over 150 miles per hour. And then the volcano exploded. With the pressure lid removed, superheated magma and gases inside the mountain erupted laterally—sideways—instead of straight up. A pyroclastic density current—a hurricane of rock, ash, and gas heated to 680°F—blasted northward at over 300 miles per hour. Faster than a commercial jet. David Johnston had seconds. He grabbed the radio and transmitted to the USGS Vancouver office: “Vancouver! Vancouver! This is it!” Those were the last words anyone heard from him. The blast wave hit Coldwater II moments later. The force was unimaginable—equivalent to multiple nuclear bombs. Trees were snapped like matchsticks. Boulders the size of cars were flung miles. The landscape was scoured down to bedrock. David Johnston, his trailer, his equipment—everything vanished. Obliterated. Fifteen seconds after his last radio call, the observation post ceased to exist.

His body was never found. The eruption simply erased him. The eruption killed 57 people that day. But it could have been thousands. The death toll would have been catastrophic if not for the work David and his colleagues had done in the weeks before. Their warnings convinced authorities to establish evacuation zones. Roadblocks prevented people from entering the most dangerous areas. Logging operations that would have had hundreds of workers in the blast zone were suspended. Harry Truman, the lodge owner who refused to evacuate, died instantly—buried under hundreds of feet of volcanic debris. So did many others who’d stayed too close. But hundreds—possibly thousands—survived because scientists like David Johnston had pushed for evacuations despite public resistance. David had given his life doing exactly what he believed scientists should do: warn people, even when those warnings are unpopular. Stay at the most dangerous observation post because someone needs to monitor the mountain up close. Risk your own safety to gather the data that might save others. In the days after the eruption, the scientific community mourned. David had been a rising star—brilliant, dedicated, beloved.

The eruption had taken him at the beginning of what should have been a long, distinguished career. But his legacy didn’t end with his death. The eruption became one of the most studied volcanic events in history. The data David and others collected revolutionized volcanology. Scientists learned how to better predict eruptions, recognize warning signs, save lives. In 1997—seventeen years after the eruption—the Johnston Ridge Observatory opened on the site where David had died. It’s a beautiful building perched on a ridge, offering visitors a direct view into the crater that killed him. Inside, exhibits explain volcanic science, the 1980 eruption, and the scientists who studied it. And it’s named for David A. Johnston—the 30-year-old scientist who stayed at his post and gave his life to understand the mountain. Today, thousands visit Johnston Ridge every year. They stand where David stood. They look at the mountain he watched. They see the landscape he saw in those final moments. And they remember that science isn’t just abstract knowledge. It’s people—real people—who risk everything to understand nature, to warn us, to keep us safe. David Johnston’s last words—”Vancouver! Vancouver! This is it!”—are etched in memory as some of the most haunting in scientific history.

Not because they were poetic or profound, but because they were exactly what a scientist should say in that moment: clear, immediate, urgent. He wasn’t thinking about himself. He was thinking about warning others. About transmitting the data. About doing his job until the very last second.Mount St. Helens still stands, though 1,300 feet shorter than before. The crater is still there—a massive scar on the mountain’s north face. Nature is slowly reclaiming the blast zone. Trees growing. Animals returning. Life rebuilding. And on Johnston Ridge, visitors can look into that crater and understand what David Johnston understood: that nature’s power is awesome, terrifying, and worthy of our deepest respect. He was 30 years old. He had his whole life ahead of him. He could have left the observation post. Could have insisted someone else take the dangerous shift. He stayed because someone needed to watch the mountain. Because the data mattered. Because warning people mattered. When the mountain finally erupted, he had seconds to live. He used them to transmit a warning. His body was never found. But his legacy endures in every volcanic observatory, every evacuation plan, every life saved by scientists who learned from what he taught us. The mountain took him. But it couldn’t take what he stood for: courage, dedication, and the belief that understanding nature’s power can save human lives. That’s not just science. That’s heroism.