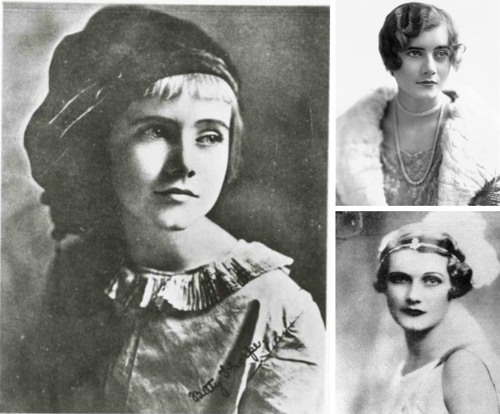

Amy Elizabeth Thorpe learned early that the world underestimated women. Born in 1910 to a Marine Corps colonel, she discovered by fourteen that beauty opened doors men thought they controlled. By nineteen, she was pregnant by one of several diplomatic lovers. She married Arthur Pack, a British diplomat nineteen years older, not for love but survival.

For years, she followed him across the world—Chile, Spain, Poland—brilliant and bored, burning for purpose. Then British intelligence noticed something. She was having an affair with a Polish official who had access to German Enigma intelligence. They asked her a simple question: would she formalize what she was already doing?

She said yes.

They gave her a codename: Cynthia.

When World War II erupted, Cynthia became one of the most effective spies in the Allied arsenal. Her method was direct—seduce men with access to secrets, extract intelligence through intimacy and manipulation. She stole Italian naval cipher books. She gathered critical intelligence on the Enigma machine.

But in 1942, British and American intelligence wanted something that could change the war: the Vichy French naval codes, locked in a safe inside their Washington embassy.

Her target was Charles Brousse—a forty-nine-year-old press attaché, decorated war hero, passionate anti-Nazi. She posed as a sympathetic journalist. Within weeks, they were lovers. For months, she gathered intelligence through pillow talk.

Then she told him the truth. She was a spy. She needed his help breaking into that safe.

He should have been horrified. Instead, he fell deeper in love.

Charles arranged for them to use the embassy after hours for romantic encounters. For weeks, they established a pattern. Guards grew accustomed to seeing them arrive, hearing passionate sounds from behind closed doors, watching them leave hours later.

Then came the real mission: break into the safe, photograph the cipher books, return everything before dawn.

They hired a professional safecracker. The plan failed twice—once because of time, once because the combination didn’t work. The third attempt would be their last chance.

On that night, the safe was open. The safecracker was photographing the cipher books. Then Cynthia heard footsteps. The night watchman—making his rounds early.

In a split second, she made her choice. She stripped off every piece of clothing except her pearl necklace. She pulled Charles close, frantically unbuttoning his shirt. The door opened.

The watchman froze. There was Cynthia—completely naked, locked in what appeared to be a passionate embrace. She didn’t try to hide. She made eye contact, her modesty deliberately careless, wanting him to see exactly what he expected to see.

The guard, mortified at interrupting what he thought was a lovers’ encounter, stammered an apology and fled.

Cynthia and the safecracker finished their work. The cipher books were photographed, returned, and locked away. No one ever knew.

In November 1942, Allied forces launched Operation Torch—the invasion of French North Africa. The stolen Vichy codes allowed them to read French naval communications, anticipate resistance, and coordinate landings with devastating precision. Operation Torch succeeded. North Africa was secured. The war’s tide began to turn.

Sir William Stephenson, who gave her the codename Cynthia, later called her the greatest unsung heroine of the war.

After the war, Arthur Pack took his own life in 1945. Charles Brousse divorced his wife and married Cynthia. They retired to his medieval château in France, where she lived quietly until her death from throat cancer in 1963.

Before she died, someone asked if she was ashamed. Her response captures everything about who she was:

“Not in the least. My superiors told me that the results of my work saved thousands of British and American lives. It involved me in situations from which respectable women draw back—but mine was total commitment. Wars are not won by respectable methods.”

History remembers James Bond—the fictional spy who seduced women for secrets. Cynthia did it first. She did it for real. She weaponized the very thing society said made women weak. And she helped win a war.