August 31, 1870. Maria Montessori was born in a small Italian town. From the beginning, she refused the path society chose for her.

While girls were expected to become teachers or wives, Maria announced she would become an engineer. When her father said no, she didn’t give up—she chose something even more impossible.

At 20, she enrolled in medical school.

She was one of the first women in Italy to study medicine. Male students hissed when she entered the lecture hall. Professors banned her from dissecting bodies alongside men. She had to work alone, at night, in cold rooms with the deceased.

She became a doctor anyway.

1896. Dr. Montessori began working in Rome’s psychiatric institutions—places where society locked away children with intellectual disabilities. Children labeled “deficient.” “Hopeless.” “Unteachable.”

What she saw broke her heart.

Children sat on bare floors with nothing to touch, nothing to explore, nothing to do. They were fed and warehoused like animals. When they misbehaved, they were punished. When they cried, they were ignored.

But Maria watched them differently.

She saw children crawling on the floor collecting breadcrumbs—not to eat, but to play with. They had no toys, no materials, nothing to occupy their desperate hands.

And she realized something shocking: These children weren’t “deficient.” They were starving for stimulation.

She began experimenting. She gave them objects to manipulate. Puzzles to solve. Materials to touch and explore.

The results stunned everyone. Children who had been written off as “unteachable” began to learn. Some even passed the same exams as “normal” children.

The medical world celebrated her success with “hopeless” children.

But Maria asked a different question: If these methods work for children with disabilities, why aren’t we using them with ALL children?

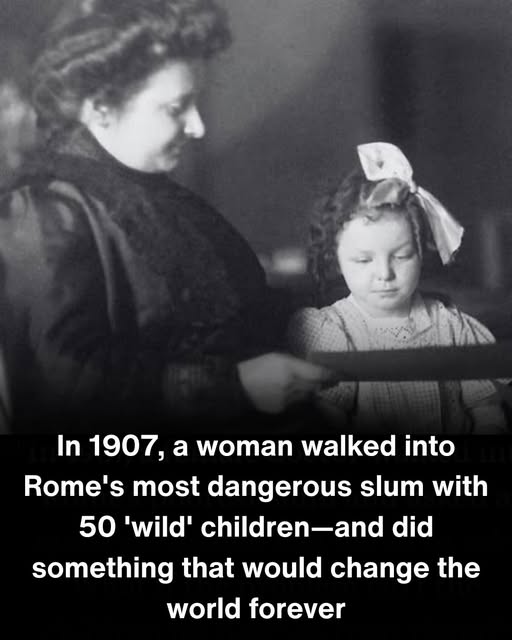

January 6, 1907. The Italian government came to her with a problem. In San Lorenzo—one of Rome’s most dangerous slums—fifty children aged 2-7 were running wild while their parents worked in factories. No school. No supervision. Nothing.

Officials wanted someone to “contain” them.

Maria Montessori saw a laboratory.

She opened Casa dei Bambini (Children’s House) with one revolutionary idea: What if children don’t need to be broken? What if they need to be understood?

Instead of desks bolted to the floor, she built child-sized furniture. Instead of punishment and fear, she created freedom within limits. Instead of demanding silence, she invited choice.

Traditional educators were horrified. “These children will destroy everything! They’ll never learn discipline!”

But something extraordinary happened.

Children who had been labeled “wild” and “uncivilized” became calm, focused, and self-directed. They chose challenging work over mindless play. They helped each other. They developed what Montessori called “inner discipline”—not obedience to authority, but mastery of themselves.

She wrote: “We do not consider an individual disciplined only when he has been rendered as artificially silent as a mute and as immovable as a paralytic. He is an individual annihilated, not disciplined.”

When a child acted out, she didn’t scold or punish. She observed. She asked: What need isn’t being met? What is this behavior trying to communicate?

Word spread like wildfire. Educators traveled from across the world to witness what seemed impossible.

1909. Montessori published The Montessori Method. It was translated into 20 languages.

1912. Alexander Graham Bell opened the first Montessori school in America. Thomas Edison installed Montessori furniture in his home.

1929. She founded the Association Montessori Internationale to train teachers worldwide.

But her influence went far beyond education. She was nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize three times (1949, 1950, 1951). Why? Because she understood that peace begins with how we treat the youngest members of society.

She wrote: “Preventing conflicts is the work of politics; establishing peace is the work of education.”

May 6, 1952. Maria Montessori died at age 81.

Today, there are over 20,000 Montessori schools in 110 countries serving millions of children.

But her most radical idea remains unchanged:

Children are not empty vessels to be filled or wild animals to be tamed. They are human beings who deserve respect, understanding, and freedom.

When modern parents say “I see you’re angry—can you tell me what happened?” they’re using Montessori’s insight: connection before correction.

When teachers create calm-down corners instead of punishment chairs, they’re honoring her belief: a calm adult becomes the child’s anchor.

When we breathe deeply with an upset child instead of yelling, we’re teaching what Montessori knew: children learn emotional regulation by watching how adults handle emotions.

Maria Montessori proved that discipline isn’t about control—it’s about guidance, patience, and respect.

She showed that even “problem” children can flourish when given dignity and the right environment.

She demonstrated that the way we treat children shapes not just their behavior, but the kind of adults—and the kind of world—they will create.

One slum in Rome. Fifty “wild” children. One woman who saw potential instead of problems.

That was all it took to change education forever.