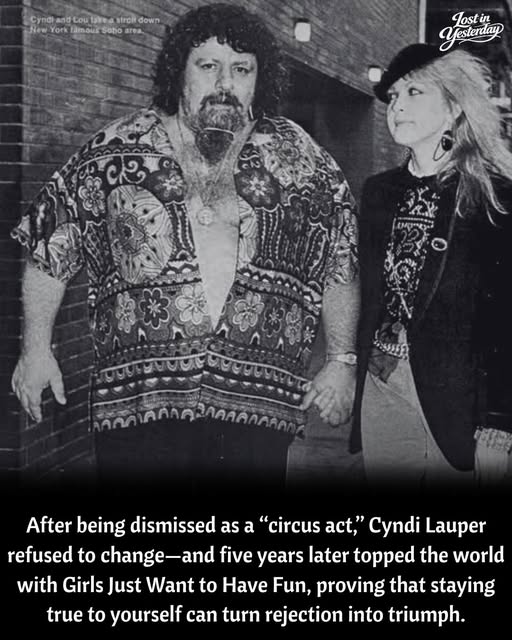

In 1978, Cyndi Lauper stood outside a New York nightclub in a crushed-velvet jacket, combat boots, and hair dyed colors most people had never seen. Her band, Blue Angel, had hauled their gear across the city for what felt like a make-or-break show. They had rehearsed obsessively. They believed in what they were doing.

The owner took one glance at them and said, “We don’t book circus acts.”

Then he closed the door.

Cyndi stayed on the curb, the cold seeping through her clothes, humiliation burning hotter than the weather. It wasn’t just a lost gig—they needed the money—but the familiar message behind it. You’re too loud. Too strange. Too much. Women weren’t supposed to look like this, sound like this, take up this much space.

She cried because she was exhausted from being told that being herself was the problem.

Her band tried to cheer her up, but they all knew the truth. This had been their story from the start. Executives told them to tone it down. Dress normal. Be less. Blue Angel didn’t fit anywhere neat, and the industry hated things it couldn’t categorize.

Cyndi wasn’t trying to be weird.

She was trying to be honest.

She grew up in Queens, raised by a single mother after her father left when she was five. Money was tight, but music filled the apartment. Judy Garland. Billie Holiday. Ella Fitzgerald. Women who sang pain and power in the same breath. Cyndi listened closely—and decided she didn’t want to sound like anyone else.

As a teenager, she bleached her hair, piled thrift-store clothes into fearless combinations, and sang anywhere she could. Diners. Dive bars. Street corners. Places that smelled like grease, cigarettes, and disappointment.

In 1979, she formed Blue Angel—a collision of rockabilly, punk, and girl-group harmonies. Labels didn’t know what to do with them. Audiences either adored them or walked out. They made one album. It failed. The band fell apart.

Cyndi was twenty-seven, broke, back to waitressing, and facing a terrifying diagnosis: damaged vocal cords. Doctors warned she might never sing professionally again.

She didn’t quit.

She relearned how to sing. Started over. Took every rejection and kept moving.

Still, the industry dismissed her. Too old. Too theatrical. Too unusual. Everything they claimed they didn’t want.

Then, in 1983, someone finally got it.

With producer Rick Chertoff, Cyndi recorded She’s So Unusual. For the first time, no one tried to sand down her edges. Her strangeness wasn’t a liability—it was the point.

She took “Girls Just Want to Have Fun,” a song written from a man’s point of view, and rewrote it into something radical: joy as rebellion. Freedom as defiance. A woman choosing herself.

In the video, she wore mismatched clothes, loud makeup, and that same wild hair—the exact look that had once gotten her laughed out of a club.

MTV played it nonstop. Radio followed. Suddenly, the girl who was “too much” had the biggest song in America.

The album kept going. “Time After Time.” “She Bop.” “All Through the Night.” “Money Changes Everything.” Four top-five hits from a debut album. A Grammy. Global fame.

And she never changed who she was.

Years later, she went back to that street. The club was gone—replaced by an upscale boutique. She laughed. “I didn’t need their stage,” she said. “I made my own.”

Cyndi never forgot the sidewalk, though. She spent her career lifting other outsiders—LGBTQ+ youth, women, anyone told they didn’t belong. She co-founded True Colors United. She wrote Kinky Boots, a story about radical acceptance, and won six Tony Awards.

She remembered what it felt like to be dismissed.

In 1978, a man looked at Cyndi Lauper and saw a joke.

Five years later, the world saw a star.

Not because she changed—but because she refused to.

Sometimes rejection isn’t a verdict. It’s a misdiagnosis.

Cyndi Lauper stayed loud, stayed colorful, stayed herself—and the world eventually caught up.