Beryl Markham was the kind of woman who made people uncomfortable.

Wives feared her. Society considered her scandalous. Hemingway himself admitted she was difficult. But even he couldn’t deny her brilliance.

Born in England in 1902, Beryl moved to British East Africa (now Kenya) as a small child. While other colonial girls learned embroidery and piano, Beryl was running wild with Maasai children, learning to hunt, and developing an obsession with horses and freedom.

By eighteen, she’d done something no woman had ever done: She became Africa’s first licensed female horse trainer. Maybe the world’s first. In 1920s Kenya, this wasn’t just unusual—it was outrageous. A teenage woman, training thoroughbred racehorses, competing in a male-dominated field, and winning.

She didn’t stop there.

In her twenties and thirties, Beryl became a bush pilot, flying mail and supplies across the African wilderness. She navigated by landmarks—rivers, mountains, elephant herds—in an era when one engine failure meant certain death.

Then, in September 1936, at age thirty-four, Beryl decided to attempt something that terrified even experienced pilots: flying solo across the Atlantic Ocean from east to west.

Here’s why that matters: Flying west to east, with the prevailing winds, was challenging but achievable. Charles Lindbergh had done it in 1927. Amelia Earhart in 1932.

But east to west? Against those same powerful headwinds? Non-stop? At night? In a single-engine plane?

No one had ever succeeded.

On September 4, 1936, Beryl climbed into her Vega Gull aircraft in England and took off into the darkness. For over twenty hours, she battled headwinds, ice, fuel concerns, and exhaustion. She couldn’t see the ocean below. She had only her instruments and her nerve.

Twenty-one hours and twenty-five minutes later, her fuel tanks nearly empty, she crash-landed in a peat bog in Nova Scotia, Canada. She’d aimed for New York but didn’t quite make it.

It didn’t matter.

Beryl Markham became the first person in history to fly solo, non-stop, east to west across the Atlantic Ocean. The “hard way.” The way everyone said was impossible.

The press went wild. Awards poured in. She was an international sensation.

And then… she mostly disappeared from public memory.

In 1942, Beryl published a memoir called “West With the Night”—a lyrical, stunning account of her life in Africa and her adventures in the sky. Critics praised it. It sold reasonably well.

Then it went out of print and was largely forgotten for four decades.

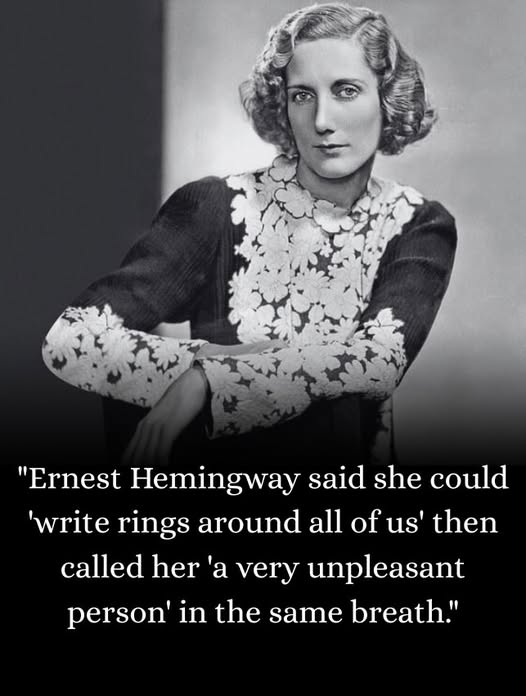

What people didn’t know was that Ernest Hemingway had written a private letter to his editor, Maxwell Perkins, about Beryl’s book. In it, he wrote:

“She has written so well, and marvelously well, that I was completely ashamed of myself as a writer… this girl, who is to my knowledge very unpleasant and we might even say a high-grade bitch, can write rings around all of us who consider ourselves as writers.”

That letter stayed hidden for years.

In 1983, someone discovered Hemingway’s praise. “West With the Night” was reprinted. Suddenly, the literary world rediscovered Beryl Markham—not just as an aviator, but as one of the finest prose stylists of her generation.

The woman Hemingway couldn’t stand had written a book he couldn’t stop thinking about.

Beryl wasn’t easy to love. She had multiple marriages and affairs. She was often broke. People called her opportunistic, difficult, cold. She made enemies as easily as she made headlines.

But she also lived by a philosophy she wrote in her memoir:

“Every tomorrow ought not to resemble every yesterday.”

She refused to be what society expected. She trained horses when women couldn’t. She flew planes when it was considered reckless. She crossed the Atlantic when experts said it was suicide. She wrote beautifully when people assumed she was just a pretty face with an adventurous streak.

Beryl Markham died in Kenya in 1986, at age eighty-three.

She was complicated. Controversial. Fearless. Brilliant. Difficult.

And she proved that you don’t have to be likable to be unforgettable.

Sometimes the people who make us most uncomfortable are the ones who show us what’s actually possible.