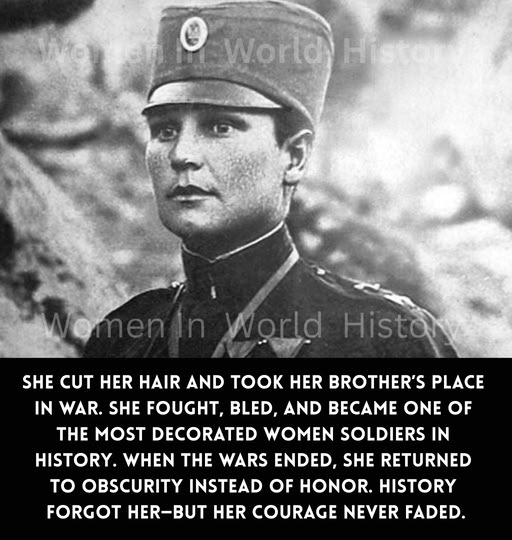

In 1912, as war pressed in on nearly every Serbian family, Milunka Savić made a choice that still sounds unreal. She learned her brother—sick and unfit to serve—had been called up anyway. So she acted. She cut her hair short, wrapped her chest, took his name, and put on a uniform that wasn’t meant for her.

It wasn’t a stunt. It wasn’t a statement for the sake of making one. It was the blunt, urgent kind of responsibility that shows up when there’s no good option—only the one you can live with.

At first, nobody suspected a thing. She drilled, marched, and fought beside men who assumed she was just another recruit. The truth only surfaced after she was hit in battle and taken for treatment. The doctors realized she was a woman, and the expectation was immediate: she’d be sent away from the front.

Milunka didn’t accept that. She went to her commanders and asked for one simple thing—let me stay. Not in a safer role. Not as a helper. As a soldier.

And, remarkably, they said yes.

From there, her service wasn’t symbolic or occasional. It was constant, punishing, and as close to the worst of the era as a person could get. She fought through the Balkan Wars and into World War I, repeatedly putting herself where the danger was thickest. She was wounded again and again—nine times, by many accounts—and each time she healed enough, she went back. People remembered her not just for bravery, but for a specific kind of bravery: getting close, fighting hand-to-hand, and dragging wounded comrades out under fire when most people would have frozen or fled.

On the battlefield, that kind of courage doesn’t stay invisible. She became one of the most decorated women soldiers in history, earning medals from Serbia and from allies like France, Russia, and Britain. Officers talked about her record with a kind of stunned respect. Reporters wrote about her like she was an exception to the rules everyone thought were fixed. She had done what society insisted women couldn’t do—and she’d done it with a toughness that outmatched plenty of men who were never questioned.

But wars end, and attention shifts.

When the fighting was over, Milunka didn’t return to a life of parades and comfort. She went back to ordinary survival—working modest jobs, raising children she adopted (including orphans of soldiers who never came home), and living quietly, far from the spotlight. For a long time, her name wasn’t widely taught or celebrated. Outside her homeland, her story could vanish with shocking ease, as if the world didn’t quite know what to do with a hero who didn’t fit the usual shape.