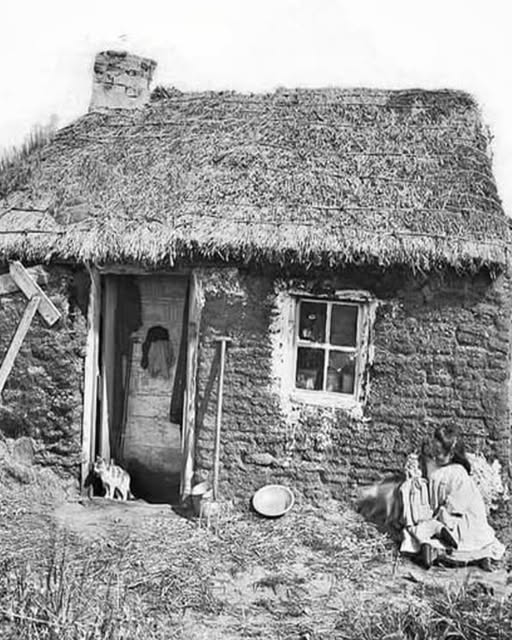

At first glance, the small sod cabin standing in County Antrim around 1900 might seem almost picturesque. Its low, rounded shape blends gently into the landscape, as if it simply grew out of the earth. To modern eyes, it can look quaint, even charming—a relic of a simpler time. But the story it tells is far from romantic.

Known in Irish as An Bothán Dóibe, these cabins were not built for nostalgia or beauty. They were built out of necessity. Families used what they had, and what they had was the land itself. Long grasses, thick with tangled roots, were cut directly from the ground in heavy slabs. These sod bricks were stacked carefully, grass-side down, row upon row, forming thick earthen walls. There was no timber frame hidden beneath, no modern insulation tucked inside. Just layers of soil, roots, and effort.

The walls went up first. Only afterward were openings hacked out for doors and windows. Planning was a luxury many could not afford. Some cabins ended up with a small window; others had none at all. Light slipped in through the doorway or through thin patches in the thatch above. When the wind blew, it found its way inside easily. When rain came—and in Ireland it often did—the dampness seeped into everything.

Inside, comfort was relative. Floors were usually packed dirt or rough stone. In winter, the cold did not merely linger in the air; it settled into bones. Families burned turf or scraps of fuel in a central hearth. Not every cabin had a chimney, so smoke often drifted upward and filtered slowly through the thatched roof, or poured out through the open door. The air would have been thick and stinging, especially on still days. Eyes watered. Clothes absorbed the smell.

At night, families slept close together on straw laid over the hard ground. The straw itself could grow damp from the moisture that crept through the walls. Those walls, though thick, were not sealed against the elements. They wept in wet weather, beads of moisture forming and slipping down their surfaces. And yet within those walls, life unfolded—children were born, meals were shared, stories were told by firelight.

By the mid-1800s, nearly 40 percent of Ireland’s rural population lived in homes like these. That number alone reshapes how we see them. These were not rare, charming cottages dotting the countryside. They were the reality for a large portion of the population, especially the poor and landless. They stood as practical shelters in a society marked by hardship, inequality, and, in time, devastating famine.

A well-built sod house could last decades, even a century, if maintained carefully. The thick earthen walls had a certain stubborn strength. But many did not survive that long. Without constant repair, rain and wind slowly wore them down. Roofs sagged. Walls slumped. Eventually, they melted back into the landscape, the soil returning to the soil. That is why so few remain today. They did not leave ruins of stone; they simply dissolved.

The cabin photographed in County Antrim survived long enough to be captured on film, but even in the image its weariness shows. A sagging wall leans slightly, as if tired from holding its shape against years of weather. The roof dips unevenly. There is no neat garden, no decorative touch. It stands plainly, honestly. Its presence speaks not of comfort, but of endurance.

It is easy, from a distance of more than a century, to soften the image of such places. We might imagine a cozy fire, a tight-knit family, a slower pace of life. And surely there were moments of warmth and connection within those walls. Human beings create love and laughter even in the harshest conditions. But it is important not to confuse resilience with ease.

These cabins existed because many families had no other option. They were a testament to resourcefulness, to the ability to shape shelter from raw earth with little more than hands and simple tools. They reflected a deep knowledge of the land—how to cut sod so that roots bound it together, how to layer it for strength. But they also reflected poverty and limited opportunity.

When we look at that little cabin now, blending into the Antrim landscape, we can allow ourselves to see its quiet beauty. There is something powerful about a home formed directly from the ground beneath it. Yet the real story lies not in its appearance, but in the lives lived inside it. The people who endured damp winters, smoky air, and hard floors were the true strength behind those walls.

The cabin is gone now, like so many others, returned to the earth that once shaped it. What remains is the reminder that survival itself can leave a legacy. Not one of comfort or glory, but of determination. And that is where the real weight of its story rests.