Her family, suddenly without their provider, couldn’t support her anymore. She went to live with her older sister and her sister’s husband, Tomio Kobashi, in Tokyo.

Tomio owned a billiard parlor.

For a young girl in 1920s Japan, this was about the worst place she could have ended up. Billiard halls weren’t respectable. They were male spaces—filled with cigarette smoke, gambling, rough characters, and the kind of atmosphere “proper” girls were taught to avoid at all costs.

But Masako had nowhere else to go.

So she stayed. And she watched.

By thirteen, she was fascinated by the games. The geometry of it. The perfect physics of ball striking ball, angles becoming trajectories, force becoming precision. By fourteen, she was working as a billiard attendant—racking balls, serving customers, cleaning tables.

And learning. Always learning.

Her brother-in-law Tomio taught her the basics. But he recognized something unusual in Masako’s focus and dedication. He arranged for her to train under Kinrey Matsuyama—one of Japan’s best three-cushion billiards champions.

What happened next became the stuff of legend.

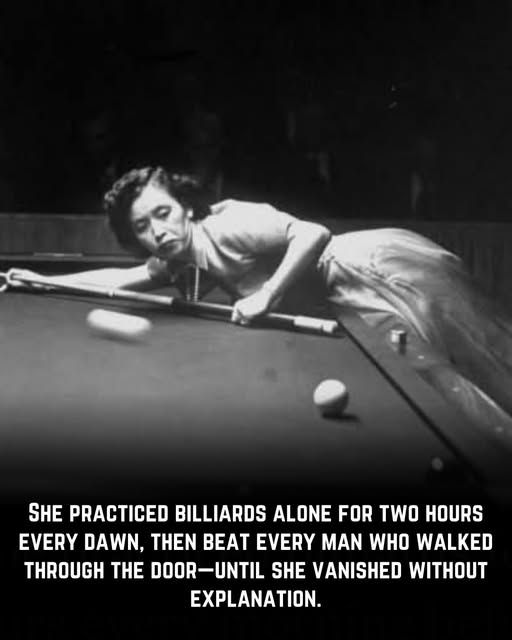

Every single morning, before the parlor opened, Masako practiced for two hours. Alone. Just her and the table and the relentless pursuit of perfection.

Then, when the doors opened and customers arrived, she played.

Six hours. Seven hours. Every day.

Man after man walked in, saw a teenage girl at the table, and assumed an easy victory. Man after man discovered they were wrong.

In an interview years later, Masako described those years in her limited English:

“I practice before parlor opens every day for two hours. Every day I practice. Soon I play with many men. Men want to beat me. I play men, six, seven hours a day. Men no like, they do not beat me. If I hit no good, my brother-in-law, after billiard parlor closed, say this shot no good. This shot bad, I make good.”

Two hours before anyone arrived. Six or seven hours against paying customers who wanted to prove a girl couldn’t beat them. Then, after closing, more practice—correcting every mistake, perfecting every weakness.

This was her life. Every day. For years.

By her twenties, Masako Katsura had become something that didn’t exist in Japan: a female professional billiards player. The only one in the entire country.

In national competitions, she finished second in Japan’s three-cushion billiards championship three times—losing only to the absolute best male players in the nation.

She had reached the ceiling of Japanese billiards. There was nowhere left to go.

Then, in 1950, Masako married Vernon Greenleaf, a U.S. Army Master Sergeant stationed in Japan. In 1951, they moved to the United States.

And everything changed.

American billiards promoters were captivated by this Japanese woman who could compete with the world’s best male players. In 1952, Masako became the first woman ever invited to compete in a world three-cushion billiards tournament.

The press called her “the First Lady of Billiards.”

She went on an exhibition tour with Welker Cochran, an eight-time world champion who’d played against the greatest players alive. After playing with Masako, Cochran made a stunning statement:

“She’s the most marvelous thing I ever saw… She’s liable to beat anybody, even Willie Hoppe… I could not see any weak spots.”

Willie Hoppe. Fifty-one-time world champion. Arguably the greatest billiards player who ever lived.

And Cochran believed Masako could beat him.

Masako toured with Hoppe himself, playing exhibition matches across America. Crowds packed billiard halls to watch this small Japanese woman execute shots with precision that rivaled the sport’s legends.

She wasn’t a novelty. She wasn’t there because promoters wanted a female face for publicity. She was there because she was genuinely, undeniably world-class.

Throughout the 1950s, Masako competed at the highest levels. She played exhibitions before major tournaments. She faced the best players in the world. Her name became known to every serious billiards enthusiast in America.

Then came 1961.

Masako played a challenge match for the World Three-Cushion Championship against Harold Worst, the reigning world champion.

She lost.

And then Masako Katsura disappeared.

No announcement. No retirement statement. No farewell tour. She simply stopped competing and vanished from professional billiards entirely.

For fifteen years, she was gone. Then, in 1976, she made a single brief, impromptu appearance at a billiards event—and disappeared again.

Around 1990, Masako moved back to Japan. On December 20, 1995, she died quietly at age 82.

To this day, no one knows exactly why she left.

Some speculate the constant pressure of being the only woman, of having to prove herself every single day, simply became too exhausting. Others suggest personal reasons related to her marriage or family. Some believe she’d accomplished everything she’d set out to do and saw no reason to continue.

The mystery remains.

But the legacy doesn’t.

Masako Katsura was the first woman to compete professionally against men in world billiards tournaments. Not because organizers lowered standards. Not because they needed diversity. But because she was good enough to belong there.

She proved, with undeniable skill, that talent has no gender.

Today, women compete in professional billiards around the world. They have their own tournaments, their own champions, their own place in the sport.

That path exists because an orphaned twelve-year-old girl ended up in a billiard parlor in 1920s Tokyo and refused to accept that the game wasn’t for her.

She practiced two hours every morning before the doors opened.

She played six or seven hours against every man who walked in thinking he’d beat her easily.

And most of the time, they left disappointed.

She became so skilled that an eight-time world champion said she could beat the greatest player who ever lived.

Then she walked away on her own terms, leaving us with a mystery we’ll never solve and a legacy we can’t ignore.

Sometimes the most revolutionary thing you can do is simply refuse to believe something isn’t for you—and then become undeniably excellent at it.

Not by demanding a place at the table.

By being too good to deny.

Masako Katsura didn’t ask for permission to break barriers.

She just practiced until no one could tell her to leave.